Vallabhbhai Patel

| Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel | |

|---|---|

| |

| 1st Deputy Prime Minister of India | |

| In office 15 August 1947 – 15 December 1950 | |

| Monarch | George VI |

| Governor General | C. Rajagopalachari |

| Prime Minister | Jawaharlal Nehru |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Morarji Desai |

| Minister of Home Affairs | |

| In office 15 August 1947 – 15 December 1950 | |

| Prime Minister | Jawaharlal Nehru |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | C. Rajagopalachari |

| 1st Commander-in-chief of the Indian Armed Forces | |

| In office 15 August 1947 – 15 December 1950 | |

| Monarch | George VI |

| Governor General | C. Rajagopalachari |

| Prime Minister | Jawaharlal Nehru |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished (merged to the President of India) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Vallabhbhai Jhaverbhai Patel 31 October 1875 Nadiad, Bombay Presidency, British India (now in Gujarat, India) |

| Died | 15 December 1950 (aged 75) Bombay, Bombay State, India (now Mumbai, Maharashtra, India) |

| Cause of death | Heart attack |

| Political party | Indian National Congress |

| Spouse(s) | Jhaverba Patel |

| Children | Maniben Patel Dahyabhai Patel |

| Mother | Ladba |

| Father | Jhaverbhai Patel |

| Alma mater | Inns of Court |

| Profession | |

| Awards | |

Vallabhbhai Patel (31 October 1875 – 15 December 1950), popularly known as Sardar Patel, was the first Deputy Prime Minister of India. He was an Indian barrister and statesman, a senior leader of the Indian National Congress and a founding father of the Republic of India who played a leading role in the country's struggle for independence and guided its integration into a united, independent nation.[1] In India and elsewhere, he was often called Sardar, Chief in Hindi, Urdu, and Persian. He acted as de facto Supreme Commander-in-chief of Indian army during the political integration of India and the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947.

Patel was born and raised in the countryside of Gujarat.[2] He was a successful lawyer. He subsequently organised peasants from Kheda, Borsad, and Bardoli in Gujarat in non-violent civil disobedience against the British Raj, becoming one of the most influential leaders in Gujarat. He rose to the leadership of the Indian National Congress, organising the party for elections in 1934 and 1937 while promoting the Quit India Movement.

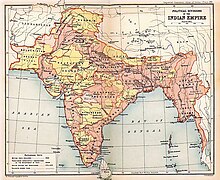

As the first Home Minister and Deputy Prime Minister of India, Patel organised relief efforts for refugees fleeing from Punjab and Delhi and worked to restore peace. He led the task of forging a united India, successfully integrating into the newly independent nation those British colonial provinces that had been "allocated" to India. Besides those provinces that had been under direct British rule, approximately 565 self-governing princely stateshad been released from British suzerainty by the Indian Independence Act of 1947. Threatening military force, Patel persuaded almost every princely state to accede to India. His commitment to national integration in the newly independent country was total and uncompromising, earning him the sobriquet "Iron Man of India".[3] He is also remembered as the "patron saint of India's civil servants" for having established the modern all-India servicessystem. He is also called the "Unifier of India".[4]

In 2014, the Government of India introduced a commemoration of Patel, held annually on his birthday, 31 October, and known as Rashtriya Ekta Diwas (National Unity Day).

Contents

Early life[edit]

Patel's date of birth was never officially recorded; Patel entered it as 31 October on his matriculation examination papers.[5] He belonged to the Leuva Patel Patidar community of Central Gujarat, although the Leuva Patels and Kadava Patels have also claimed him as one of their own.[6]

Patel travelled to attend schools in Nadiad, Petlad, and Borsad, living self-sufficiently with other boys. He reputedly cultivated a stoic character. A popular anecdote recounts that he lanced his own painful boil without hesitation, even as the barber charged with doing it trembled.[7] When Patel passed his matriculation at the relatively late age of 22, he was generally regarded by his elders as an unambitious man destined for a commonplace job. Patel himself, though, harboured a plan to study to become a lawyer, work and save funds, travel to England, and become a barrister.[8] Patel spent years away from his family, studying on his own with books borrowed from other lawyers, passing his examinations within two years. Fetching his wife Jhaverba from her parents' home, Patel set up his household in Godhra and was called to the bar. During the many years it took him to save money, Patel – now an advocate – earned a reputation as a fierce and skilled lawyer. The couple had a daughter, Maniben, in 1904 and a son, Dahyabhai, in 1906. Patel also cared for a friend suffering from the Bubonic plague when it swept across Gujarat. When Patel himself came down with the disease, he immediately sent his family to safety, left his home, and moved into an isolated house in Nadiad (by other accounts, Patel spent this time in a dilapidated temple); there, he recovered slowly.[9]

Patel practised law in Godhra, Borsad, and Anand while taking on the financial burdens of his homestead in Karamsad. Patel was the first chairman and founder of "Edward Memorial High School" Borsad, today known as Jhaverbhai Dajibhai Patel High School. When he had saved enough for his trip to England and applied for a pass and a ticket, they were addressed to "V. J. Patel," at the home of his elder brother Vithalbhai, who had the same initials as Vallabhai. Having once nurtured a similar hope to study in England, Vithalbhai remonstrated his younger brother, saying that it would be disreputable for an older brother to follow his younger brother. In keeping with concerns for his family's honour, Patel allowed Vithalbhai to go in his place.[10]

In 1909 Patel's wife Jhaverba was hospitalised in Bombay (now Mumbai) to undergo major surgery for cancer. Her health suddenly worsened and, despite successful emergency surgery, she died in the hospital. Patel was given a note informing him of his wife's demise as he was cross-examining a witness in court. According to witnesses, Patel read the note, pocketed it, and continued his cross-examination and won the case. He broke the news to others only after the proceedings had ended.[11] Patel decided against marrying again. He raised his children with the help of his family and sent them to English-language schools in Mumbai. At the age of 36 he journeyed to England and enrolled at the Middle Temple Inn in London. Completing a 36-month course in 30 months, Patel finished at the top of his class despite having had no previous college background.[12]

Returning to India, Patel settled in Ahmedabad and became one of the city's most successful barristers. Wearing European-style clothes and sporting urbane mannerisms, he became a skilled bridge player. Patel nurtured ambitions to expand his practice and accumulate great wealth and to provide his children with a modern education. He had made a pact with his brother Vithalbhai to support his entry into politics in the Bombay Presidency, while Patel remained in Ahmedabad to provide for the family.[13][14]

Fight for self-rule[edit]

At the urging of his friends, Patel ran in the election for the post of sanitation commissioner of Ahmedabad in 1917 and won. While often clashing with British officials on civic issues, he did not show any interest in politics. Upon hearing of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, he joked to the lawyer and political activist, Ganesh Vasudev Mavlankar, that "Gandhi would ask you if you know how to shift pebbles from wheat. And that is supposed to bring independence." A subsequent meeting with Gandhi, in October 1917 fundamentally changed Patel and led him to join the Indian independence struggle.[15]

In September 1917, Patel had already a speech in Borsad, encouraging Indians nationwide to sign Gandhi's petition demanding Swaraj – self-rule – from Britain. A month later, he met Gandhi for the first time at the Gujarat Political Conference in Godhra. On Gandhi's encouragement, Patel became the secretary of the Gujarat Sabha, a public body that would become the Gujarati arm of the Indian National Congress. Patel now energetically fought against veth – the forced servitude of Indians to Europeans – and organised relief efforts in the wake of plague and famine in Kheda.[16] The Kheda peasants' plea for exemption from taxation had been turned down by British authorities. Gandhi endorsed waging a struggle there, but could not lead it himself due to his activities in Champaran. When Gandhi asked for a Gujarati activist to devote himself completely to the assignment, Patel volunteered, much to Gandhi's delight.[17] Though his decision was made on the spot, Patel later said that his desire and commitment came after intense personal contemplation, as he realised he would have to abandon his career and material ambitions.[18]

Satyagraha in Gujarat[edit]

Supported by Congress volunteers Narhari Parikh, Mohanlal Pandya, and Abbas Tyabji, Vallabhbhai Patel began a village-by-village tour in the Kheda district, documenting grievances and asking villagers for their support for a statewide revolt by refusing to pay taxes. Patel emphasised the potential hardships and the need for complete unity and non-violence in the face of provocation. He received an enthusiastic response from virtually every village.[19]When the revolt was launched and tax revenue withheld, the government sent police and intimidation squads to seize property, including confiscating barn animals and whole farms. Patel organised a network of volunteers to work with individual villages, helping them hide valuables and protect themselves against raids. Thousands of activists and farmers were arrested, but Patel was not. The revolt evoked sympathy and admiration across India, including among pro-British Indian politicians. The government agreed to negotiate with Patel and decided to suspend the payment of taxes for a year, even scaling back the rate. Patel emerged as a hero to Gujaratis.[20] In 1920 he was elected president of the newly formed Gujarat Pradesh Congress Committee; he would serve as its president until 1945.[citation needed]

Patel supported Gandhi's non-cooperation Movement and toured the state to recruit more than 300,000 members and raise over Rs. 1.5 million in funds.[21] Helping organise bonfires in Ahmedabad in which British goods were burned, Patel threw in all his English-style clothes. Along with his daughter Mani and son Dahya, he switched completely to wearing khadi, the locally produced cotton clothing. Patel also supported Gandhi's controversial suspension of resistance in the wake of the Chauri Chaura incident. In Gujarat he worked extensively in the following years against alcoholism, untouchability, and caste discrimination, as well as for the empowerment of women. In the Congress, he was a resolute supporter of Gandhi against his Swarajist critics. Patel was elected Ahmedabad's municipal president in 1922, 1924, and 1927; during his terms, he oversaw improvements in infrastructure: the supply of electricity was increased, and drainage and sanitation systems were extended throughout the city. The school system underwent major reforms. He fought for the recognition and payment of teachers employed in schools established by nationalists (independent of British control) and even took on sensitive Hindu–Muslim issues.[22] Patel personally led relief efforts in the aftermath of the torrential rainfall of 1927 that caused major floods in the city and in the Kheda district, and great destruction of life and property. He established refugee centres across the district, mobilized volunteers, and arranged for supplies of food, medicines, and clothing, as well as emergency funds from the government and the public.[23]

When Gandhi was in prison, Patel was asked by Members of Congress to lead the satyagraha in Nagpur in 1923 against a law banning the raising of the Indian flag. He organised thousands of volunteers from all over the country to take part in processions of people violating the law. Patel negotiated a settlement obtaining the release of all prisoners and allowing nationalists to hoist the flag in public. Later that year, Patel and his allies uncovered evidence suggesting that the police were in league with local dacoits (Devar Baba) in the Borsad taluka even as the government prepared to levy a major tax for fighting dacoits in the area. More than 6,000 villagers assembled to hear Patel speak in support of proposed agitation against the tax, which was deemed immoral and unnecessary. He organised hundreds of Congressmen, sent instructions, and received information from across the district. Every village in the taluka resisted payment of the tax and prevented the seizure of property and land. After a protracted struggle, the government withdrew the tax. Historians believe that one of Patel's key achievements was the building of cohesion and trust amongst the different castes and communities, which had been divided along socio-economic lines.[24]

In April 1928 Patel returned to the independence struggle from his municipal duties in Ahmedabad when Bardoli suffered from a serious double predicament of a famine and a steep tax hike. The revenue hike was steeper than it had been in Kheda even though the famine covered a large portion of Gujarat. After cross-examining and talking to village representatives, emphasising the potential hardship and need for non-violence and cohesion, Patel initiated the struggle with a complete denial of taxes.[25] Patel organised volunteers, camps, and an information network across affected areas. The revenue refusal was stronger than in Kheda, and many sympathy satyagrahas were undertaken across Gujarat. Despite arrests and seizures of property and land, the struggle intensified. The situation came to a head in August, when, through sympathetic intermediaries, he negotiated a settlement that included repealing the tax hike, reinstating village officials who had resigned in protest, and returning seized property and land. It was women of bardoli during the struggle and after the victory in Bardoli that Patel was increasingly addressed by his colleagues and followers as Sardar.[26]

As Gandhi embarked on the Dandi Salt March, Patel was arrested in the village of Ras and was put on trial without witnesses, with no lawyer or journalists allowed to attend. Patel's arrest and Gandhi's subsequent arrest caused the Salt Satyagraha to greatly intensify in Gujarat – districts across Gujarat launched an anti-tax rebellion until and unless Patel and Gandhi were released.[27] Once released, Patel served as interim Congress president, but was re-arrested while leading a procession in Mumbai. After the signing of the Gandhi–Irwin Pact, Patel was elected president of Congress for its 1931 session in Karachi – here the Congress ratified the pact and committed itself to the defence of fundamental rights and civil liberties. It advocated the establishment of a secular nation with a minimum wage and the abolition of untouchability and serfdom. Patel used his position as Congress president to organise the return of confiscated land to farmers in Gujarat.[28] Upon the failure of the Round Table Conference in London, Gandhi and Patel were arrested in January 1932 when the struggle re-opened, and imprisoned in the Yeravda Central Jail. During this term of imprisonment, Patel and Gandhi grew close to each other, and the two developed a close bond of affection, trust, and frankness. Their mutual relationship could be described as that of an elder brother (Gandhi) and his younger brother (Patel). Despite having arguments with Gandhi, Patel respected his instincts and leadership. In prison, the two discussed national and social issues, read Hindu epics, and cracked jokes. Gandhi taught Patel Sanskrit. Gandhi's secretary, Mahadev Desai, kept detailed records of conversations between Gandhi and Patel.[29] When Gandhi embarked on a fast-unto-death protesting the separate electorates allocated for untouchables, Patel looked after Gandhi closely and himself refrained from partaking of food.[30] Patel was later moved to a jail in Nasik, and refused a British offer for a brief release to attend the cremation of his brother Vithalbhai, who had died in 1934. He was finally released in July of the same year.[citation needed]

Patel's position at the highest level in the Congress was largely connected with his role from 1934 onwards (when the Congress abandoned its boycott of elections) in the party organisation. Based at an apartment in Mumbai, he became the Congress's main fundraiser and chairman of its Central Parliamentary Board, playing the leading role in selecting and financing candidates for the 1934 elections to the Central Legislative Assembly in New Delhi and for the provincial elections of 1936.[31] In addition to collecting funds and selecting candidates, he also determined the Congress's stance on issues and opponents.[32] Not contesting a seat for himself, Patel nevertheless guided Congressmen elected in the provinces and at the national level. In 1935 Patel underwent surgery for haemorrhoids, yet continued to direct efforts against the plague in Bardoli and again when a drought struck Gujarat in 1939. Patel guided the Congress ministries that had won power across India with the aim of preserving party discipline – Patel feared that the British would take advantage of opportunities to create conflict among elected Congressmen, and he did not want the party to be distracted from the goal of complete independence.[33] Patel clashed with Nehru, opposing declarations of the adoption of socialism at the 1936 Congress session, which he believed was a diversion from the main goal of achieving independence. In 1938 Patel organised rank and file opposition to the attempts of then-Congress president Subhas Chandra Bose to move away from Gandhi's principles of non-violent resistance. Patel saw Bose as wanting more power over the party. He led senior Congress leaders in a protest that resulted in Bose's resignation. But criticism arose from Bose's supporters, socialists, and other Congressmen that Patel himself was acting in an authoritarian manner in his defence of Gandhi's authority.[citation needed]

Quit India[edit]

On the outbreak of World War II, Patel supported Nehru's decision to withdraw the Congress from central and provincial legislatures, contrary to Gandhi's advice, as well as an initiative by senior leader Chakravarthi Rajagopalachari to offer Congress's full support to Britain if it promised Indian independence at the end of the war and installed a democratic government right away. Gandhi had refused to support Britain on the grounds of his moral opposition to war, while Subhash Chandra Bose was in militant opposition to the British. The British rejected Rajagopalachari's initiative, and Patel embraced Gandhi's leadership again.[34] He participated in Gandhi's call for individual disobedience, and was arrested in 1940 and imprisoned for nine months. He also opposed the proposals of the Cripps' mission in 1942. Patel lost more than twenty pounds during his period in jail.[citation needed]

While Nehru, Rajagopalachari, and Maulana Azad initially criticised Gandhi's proposal for an all-out campaign of civil disobedience to force the British to quit India, Patel was its most fervent supporter. Arguing that the British would retreat from India as they had from Singapore and Burma, Patel urged that the campaign start without any delay.[35] Though feeling that the British would not leave immediately, Patel favoured an all-out rebellion that would galvanise the Indian people, who had been divided in their response to the war, In Patel's view, such a rebellion would force the British to concede that continuation of colonial rule had no support in India, and thus speed the transfer of power to Indians.[36] Believing strongly in the need for revolt, Patel stated his intention to resign from the Congress if the revolt were not approved.[37] Gandhi strongly pressured the All India Congress Committee to approve an all-out campaign of civil disobedience, and the AICC approved the campaign on 7 August 1942. Though Patel's health had suffered during his stint in jail, he gave emotional speeches to large crowds across India,[38] asking them to refuse to pay taxes and to participate in civil disobedience, mass protests, and a shutdown of all civil services. He raised funds and prepared a second tier of command as a precaution against the arrest of national leaders.[39] Patel made a climactic speech to more than 100,000 people gathered at Gowalia Tank in Bombay (Mumbai) on 7 August:

Historians believe that Patel's speech was instrumental in electrifying nationalists, who up to then had been skeptical of the proposed rebellion. Patel's organising work in this period is credited by historians with ensuring the success of the rebellion across India.[41] Patel was arrested on 9 August and was imprisoned with the entire Congress Working Committee from 1942 to 1945 at the fort in Ahmednagar. Here he spun cloth, played bridge, read a large number of books, took long walks, and practised gardening. He also provided emotional support to his colleagues while awaiting news and developments from the outside.[42] Patel was deeply pained at the news of the deaths of Mahadev Desai and Kasturba Gandhi later that year.[43] But Patel wrote in a letter to his daughter that he and his colleagues were experiencing "fullest peace" for having done "their duty".[44] Even though other political parties had opposed the struggle and the British had employed ruthless means of suppression, the Quit India movement was "by far the most serious rebellion since that of 1857", as the viceroy cabled to Winston Churchill. More than 100,000 people were arrested and many were killed in violent struggles with the police. Strikes, protests, and other revolutionary activities had broken out across India.[45]When Patel was released on 15 June 1945, he realised that the British were preparing proposals to transfer power to India.[citation needed]

Integration after Independence and role of Gandhi[edit]

In the 1946 election for the Congress presidency, the nominations were to be made by 15 state/regional Congress committees. Despite Gandhi's well-known preference for Nehru as Congress president, not a single Congress committee nominated Nehru's name. 12 out of 15 Congress committees nominated Sardar Vallabh Bhai Patel. The remaining three Congress committees did not nominate any body's name. The majority was in favour of Sardar Patel. Mahatma Gandhi told Acharya J B kriplani to get some proposers for Nehru from the Congress Working Committee (CWC) members despite knowing fully well that only Pradesh Congress Committees were authorized to nominate the president. In deference to Gandhi's wish, Kripalani convinced a few CWC members to propose Nehru's name for party president. Later, Mahatma Gandhi tried to make Nehru understand the reality. He conveyed to Nehru that no PCC has nominated his name and that only a few CWC members have nominated him but Nehru was defiant and made it clear that he will not play second fiddle to any body. Thus, Patel stepped down in favour of Nehru at the request of Gandhi.[46] The election's importance stemmed from the fact that the elected president would lead independent India's first government. As the first Home Minister, Patel played a key role in the integration of the princely states into the Indian federation.

In the elections, the Congress won a large majority of the elected seats, dominating the Hindu electorate. But the Muslim League led by Muhammad Ali Jinnah won a large majority of Muslim electorate seats. The League had resolved in 1940 to demand Pakistan – an independent state for Muslims – and was a fierce critic of the Congress. The Congress formed governments in all provinces save Sindh, Punjab, and Bengal, where it entered into coalitions with other parties.

Cabinet mission and partition[edit]

When the British mission proposed two plans for transfer of power, there was considerable opposition within the Congress to both. The plan of 16 May 1946 proposed a loose federation with extensive provincial autonomy, and the "grouping" of provinces based on religious-majority. The plan of 16 May 1946 proposed the partition of India on religious lines, with over 565 princely states free to choose between independence or accession to either dominion. The League approved both plans while the Congress flatly rejected the proposal of 16 May. Gandhi criticised the 16 May proposal as being inherently divisive, but Patel, realising that rejecting the proposal would mean that only the League would be invited to form a government, lobbied the Congress Working Committee hard to give its assent to the 16 May proposal. Patel engaged the British envoys Sir Stafford Cripps and Lord Pethick-Lawrence and obtained an assurance that the "grouping" clause would not be given practical force, Patel converted Jawaharlal Nehru, Rajendra Prasad, and Rajagopalachari to accept the plan. When the League retracted its approval of the 16 May plan, the viceroy Lord Wavell invited the Congress to form the government. Under Nehru, who was styled the "Vice President of the Viceroy's Executive Council", Patel took charge of the departments of home affairs and information and broadcasting. He moved into a government house on Aurangzeb Road in Delhi, which would be his home until his death in 1950.[47]

Vallabhbhai Patel was one of the first Congress leaders to accept the partition of India as a solution to the rising Muslim separatist movement led by Muhammad Ali Jinnah. He had been outraged by Jinnah's Direct Action campaign, which had provoked communal violence across India, and by the viceroy's vetoes of his home department's plans to stop the violence on the grounds of constitutionality. Patel severely criticised the viceroy's induction of League ministers into the government, and the revalidation of the grouping scheme by the British without Congress's approval. Although further outraged at the League's boycott of the assembly and non-acceptance of the plan of 16 May despite entering government, he was also aware that Jinnah did enjoy popular support amongst Muslims, and that an open conflict between him and the nationalists could degenerate into a Hindu-Muslim civil war of disastrous consequences. The continuation of a divided and weak central government would, in Patel's mind, result in the wider fragmentation of India by encouraging more than 600 princely states towards independence.[48] In December 1946 and January 1947, Patel worked with civil servant V. P. Menon on the latter's suggestion for a separate dominion of Pakistan created out of Muslim-majority provinces. Communal violence in Bengal and Punjab in January and March 1947 further convinced Patel of the soundness of partition. Patel, a fierce critic of Jinnah's demand that the Hindu-majority areas of Punjab and Bengal be included in a Muslim state, obtained the partition of those provinces, thus blocking any possibility of their inclusion in Pakistan. Patel's decisiveness on the partition of Punjab and Bengal had won him many supporters and admirers amongst the Indian public, which had tired of the League's tactics, but he was criticised by Gandhi, Nehru, secular Muslims, and socialists for a perceived eagerness to do so. When Lord Louis Mountbatten formally proposed the plan on 3 June 1947, Patel gave his approval and lobbied Nehru and other Congress leaders to accept the proposal. Knowing Gandhi's deep anguish regarding proposals of partition, Patel engaged him in frank discussion in private meetings over what he saw as the practical unworkability of any Congress–League coalition, the rising violence, and the threat of civil war. At the All India Congress Committee meeting called to vote on the proposal, Patel said:

After Gandhi rejected and Congress approved – the plan, Patel represented India on the Partition Council,[50][51] where he oversaw the division of public assets, and selected the Indian council of ministers with Nehru.[52] However, neither Patel nor any other Indian leader had foreseen the intense violence and population transfer that would take place with partition. Patel took the lead in organising relief and emergency supplies, establishing refugee camps, and visiting the border areas with Pakistani leaders to encourage peace. Despite these efforts, the death toll is estimated at between 500,000 and 1 million people.[53] The estimated number of refugees in both countries exceeds 15 million.[54] Understanding that Delhi and Punjab policemen, accused of organising attacks on Muslims, were personally affected by the tragedies of partition, Patel called out the Indian Army with South Indian regiments to restore order, imposing strict curfews and shoot-at-sight orders. Visiting the Nizamuddin Auliya Dargah area in Delhi, where thousands of Delhi Muslims feared attacks, he prayed at the shrine, visited the people, and reinforced the presence of police. He suppressed from the press reports of atrocities in Pakistan against Hindus and Sikhs to prevent retaliatory violence. Establishing the Delhi Emergency Committee to restore order and organising relief efforts for refugees in the capital, Patel publicly warned officials against partiality and neglect. When reports reached Patel that large groups of Sikhs were preparing to attack Muslim convoys heading for Pakistan, Patel hurried to Amritsar and met Sikh and Hindu leaders. Arguing that attacking helpless people was cowardly and dishonourable, Patel emphasised that Sikh actions would result in further attacks against Hindus and Sikhs in Pakistan. He assured the community leaders that if they worked to establish peace and order and guarantee the safety of Muslims, the Indian government would react forcefully to any failures of Pakistan to do the same. Additionally, Patel addressed a massive crowd of approximately 200,000 refugees who had surrounded his car after the meetings:

Following his dialogue with community leaders and his speech, no further attacks occurred against Muslim refugees, and a wider peace and order was soon re-established over the entire area. However, Patel was criticised by Nehru, secular Muslims, and Gandhi over his alleged wish to see Muslims from other parts of India depart. While Patel vehemently denied such allegations, the acrimony with Maulana Azad and other secular Muslim leaders increased when Patel refused to dismiss Delhi's Sikh police commissioner, who was accused of discrimination. Hindu and Sikh leaders also accused Patel and other leaders of not taking Pakistan sufficiently to task over the attacks on their communities there, and Muslim leaders further criticised him for allegedly neglecting the needs of Muslims leaving for Pakistan, and concentrating resources for incoming Hindu and Sikh refugees. Patel clashed with Nehru and Azad over the allocation of houses in Delhi vacated by Muslims leaving for Pakistan; Nehru and Azad desired to allocate them for displaced Muslims, while Patel argued that no government professing secularism must make such exclusions. However, Patel was publicly defended by Gandhi and received widespread admiration and support for speaking frankly on communal issues and acting decisively and resourcefully to quell disorder and violence.[56]

Political integration of India[edit]

This event formed the cornerstone of Patel's popularity in the post-independence era. Even today he is remembered as the man who united India. He is, in this regard, compared to Otto von Bismarck of Germany, who did the same thing in the 1860s. Under the plan of 3 June, more than 562 princely states were given the option of joining either India or Pakistan, or choosing independence. Indian nationalists and large segments of the public feared that if these states did not accede, most of the people and territory would be fragmented. The Congress as well as senior British officials considered Patel the best man for the task of achieving unification of the princely states with the Indian dominion. Gandhi had said to Patel, "[T]he problem of the States is so difficult that you alone can solve it".[57] Patel was considered a statesman of integrity with the practical acumen and resolve to accomplish a monumental task. He asked V. P. Menon, a senior civil servant with whom he had worked on the partition of India, to become his right-hand man as chief secretary of the States Ministry. On 6 May 1947, Patel began lobbying the princes, attempting to make them receptive towards dialogue with the future government and forestall potential conflicts. Patel used social meetings and unofficial surroundings to engage most of the monarchs, inviting them to lunch and tea at his home in Delhi. At these meetings, Patel explained that there was no inherent conflict between the Congress and the princely order. Patel invoked the patriotism of India's monarchs, asking them to join in the independence of their nation and act as responsible rulers who cared about the future of their people. He persuaded the princes of 565 states of the impossibility of independence from the Indian republic, especially in the presence of growing opposition from their subjects. He proposed favourable terms for the merger, including the creation of privy purses for the rulers' descendants. While encouraging the rulers to act out of patriotism, Patel did not rule out force. Stressing that the princes would need to accede to India in good faith, he set a deadline of 15 August 1947 for them to sign the instrument of accession document. All but three of the states willingly merged into the Indian union; only Jammu and Kashmir, Junagadh, and Hyderabad did not fall into his basket.[58]

Junagadh was especially important to Patel, since it was in his home state of Gujarat. It was also important because in this Kathiawar district was the ultra-rich Somnath temple (which in the 11th century had been plundered by Mahmud of Ghazni, who damaged the temple and its idols to rob it of its riches, including emeralds, diamonds, and gold). Under pressure from Sir Shah Nawaz Bhutto, the Nawab had acceded to Pakistan. It was, however, quite far from Pakistan, and 80% of its population was Hindu. Patel combined diplomacy with force, demanding that Pakistan annul the accession, and that the Nawab accede to India. He sent the Army to occupy three principalities of Junagadh to show his resolve. Following widespread protests and the formation of a civil government, or Aarzi Hukumat, both Bhutto and the Nawab fled to Karachi, and under Patel's orders the Indian Army and police units marched into the state. A plebiscite organised later produced a 99.5% vote for merger with India.[59] In a speech at the Bahauddin College in Junagadh following the latter's take-over, Patel emphasised his feeling of urgency on Hyderabad, which he felt was more vital to India than Kashmir:

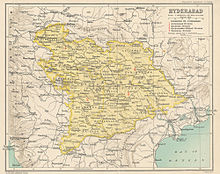

Hyderabad was the largest of the princely states, and it included parts of present-day Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and Maharashtra states. Its ruler, the Nizam Osman Ali Khan, was a Muslim, although over 80% of its people were Hindu. The Nizam sought independence or accession with Pakistan. Muslim forces loyal to Nizam, called the Razakars, under Qasim Razvi, pressed the Nizam to hold out against India, while organising attacks on people on Indian soil. Even though a Standstill Agreement was signed due to the desperate efforts of Lord Mountbatten to avoid a war, the Nizam rejected deals and changed his positions.[60] In September 1948 Patel emphasised in Cabinet meetings that India should talk no more, and reconciled Nehru and the Governor-General, Chakravarti Rajgopalachari, to military action. Following preparations, Patel ordered the Indian Army to invade Hyderabad (in his capacity as Acting Prime Minister) when Nehru was touring Europe.[61] The action was termed Operation Polo, and thousands of Razakar forces were killed, but Hyderabad was forcefully secured and integrated into the Indian Union.[62] The main aim of Mountbatten and Nehru in avoiding a forced annexation was to prevent an outbreak of Hindu–Muslim violence. Patel insisted that if Hyderabad were allowed to continue as an independent nation enclave surrounded by India, the prestige of the government would fall, and then neither Hindus nor Muslims would feel secure in its realm. After defeating Nizam, Patel retained him as the ceremonial chief of state, and held talks with him.[63]There were 562 princely states in India which Sardar Patel unified.

Leading India[edit]

The Governor-General of India, Chakravarti Rajagopalachari, along with Nehru and Patel, formed the "triumvirate" that ruled India from 1948 to 1950. Prime Minister Nehru was intensely popular with the masses, but Patel enjoyed the loyalty and the faith of rank and file Congressmen, state leaders, and India's civil servants. Patel was a senior leader in the Constituent Assembly of India and was responsible in large measure for shaping India's constitution. He is also known as the "Bismarck of India".[64] Patel was a key force behind the appointment of Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar as the chairman of the drafting committee, and the inclusion of leaders from a diverse political spectrum in the process of writing the constitution.[64]

Patel was the chairman of the committees responsible for minorities, tribal and excluded areas, fundamental rights, and provincial constitutions. Patel piloted a model constitution for the provinces in the Assembly, which contained limited powers for the state governor, who would defer to the president – he clarified it was not the intention to let the governor exercise power that could impede an elected government.[64] He worked closely with Muslim leaders to end separate electorates and the more potent demand for reservation of seats for minorities.[65] Patel held personal dialogues with leaders of other minorities on the question, and was responsible for the measure that allows the president to appoint Anglo-Indians to Parliament. His intervention was key to the passage of two articles that protected civil servants from political involvement and guaranteed their terms and privileges.[64] He was also instrumental in the founding the Indian Administrative Service and the Indian Police Service, and for his defence of Indian civil servants from political attack; he is known as the "patron saint" of India's services. When a delegation of Gujarati farmers came to him citing their inability to send their milk production to the markets without being fleeced by intermediaries, Patel exhorted them to organise the processing and sale of milk by themselves, and guided them to create the Kaira District Co-operative Milk Producers' Union Limited, which preceded the Amul milk products brand. Patel also pledged the reconstruction of the ancient but dilapidated Somnath Temple in Saurashtra. He oversaw the restoration work and the creation of a public trust, and pledged to dedicate the temple upon the completion of work (the work was completed after his death and the temple was inaugurated by the first President of India, Dr. Rajendra Prasad).

When the Pakistani invasion of Kashmir began in September 1947, Patel immediately wanted to send troops into Kashmir. But, agreeing with Nehru and Mountbatten, he waited until Kashmir's monarch had acceded to India. Patel then oversaw India's military operations to secure Srinagar and the Baramulla Pass, and the forces retrieved much territory from the invaders. Patel, along with Defence Minister Baldev Singh, administered the entire military effort, arranging for troops from different parts of India to be rushed to Kashmir and for a major military road connecting Srinagar to Pathankot to be built in six months.[66] Patel strongly advised Nehru against going for arbitration to the United Nations, insisting that Pakistan had been wrong to support the invasion and the accession to India was valid. He did not want foreign interference in a bilateral affair. Patel opposed the release of Rs. 550 million to the Government of Pakistan, convinced that the money would go to finance the war against India in Kashmir. The Cabinet had approved his point but it was reversed when Gandhi, who feared an intensifying rivalry and further communal violence, went on a fast-unto-death to obtain the release. Patel, though not estranged from Gandhi, was deeply hurt at the rejection of his counsel and a Cabinet decision.[67]

In 1949 a crisis arose when the number of Hindu refugees entering West Bengal, Assam, and Tripura from East Pakistan climbed to over 800,000. The refugees in many cases were being forcibly evicted by Pakistani authorities, and were victims of intimidation and violence.[68] Nehru invited Liaquat Ali Khan, Prime Minister of Pakistan, to find a peaceful solution. Despite his aversion, Patel reluctantly met Khan and discussed the matter. Patel strongly criticised Nehru's plan to sign a pact that would create minority commissions in both countries and pledge both India and Pakistan to a commitment to protect each other's minorities.[69] Syama Prasad Mookerjee and K. C. Neogy, two Bengali ministers, resigned, and Nehru was intensely criticised in West Bengal for allegedly appeasing Pakistan. The pact was immediately in jeopardy. Patel, however, publicly came to Nehru's aid. He gave emotional speeches to members of Parliament, and the people of West Bengal, and spoke with scores of delegations of Congressmen, Hindus, Muslims, and other public interest groups, persuading them to give peace a final effort.[70]

In April 2015 the Government of India declassified surveillance reports suggesting that Patel, while Home Minister, and Nehru were among officials involved in alleged government-authorised spying on the family of Subhas Chandra Bose.[71]

Father of modern All India Services[edit]

| “ | There is no alternative to this administrative system... The Union will go, you will not have a united India if you do not have good All-India Service which has the independence to speak out its mind, which has sense of security that you will standby your work... If you do not adopt this course, then do not follow the present Constitution. Substitute something else... these people are the instrument. Remove them and I see nothing but a picture of chaos all over the country. | ” |

| — Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel in Constituent Assembly discussing the role of All India Services., [72][73][74] | ||

He was also instrumental in the creation of the All India Services which he described as the country’s "Steel Frame". In his address to the probationers of these services, he asked them to be guided by the spirit of service in day-to-day administration. He reminded them that the ICS was no longer neither Imperial, nor civil, nor imbued with any spirit of service after Independence. His exhortation to the probationers to maintain utmost impartiality and incorruptibility of administration is as relevant today as it was then. "A civil servant cannot afford to, and must not, take part in politics. Nor must he involve himself in communal wrangles. To depart from the path of rectitude in either of these respects is to debase public service and to lower its dignity," he had cautioned them on 21 April 1947.[75]

He, more than anyone else in post-independence India, realized the crucial role that civil services play in administering a country, in not merely maintaining law and order, but running the institutions that provide the binding cement to a society. He, more than any other contemporary of his, was aware of the needs of a sound, stable administrative structure as the lynchpin of a functioning polity. The present-day all-India administrative services owe their origin to the man’s sagacity and thus he is regarded as Father of modern All India Services.[76]

Gandhi's death and relations with Nehru[edit]

Patel was intensely loyal to Gandhi, and both he and Nehru looked to him to arbitrate disputes. However, Nehru and Patel sparred over national issues. When Nehru asserted control over Kashmir policy, Patel objected to Nehru's sidelining his home ministry's officials.[77]Nehru was offended by Patel's decision-making regarding the states' integration, having consulted neither him nor the Cabinet. Patel asked Gandhi to relieve him of his obligation to serve, believing that an open political battle would hurt India. After much personal deliberation and contrary to Patel's prediction, Gandhi on 30 January 1948 told Patel not to leave the government. A free India, according to Gandhi, needed both Patel and Nehru. Patel was the last man to privately talk with Gandhi, who was assassinated just minutes after Patel's departure.[78] At Gandhi's wake, Nehru and Patel embraced each other and addressed the nation together. Patel gave solace to many associates and friends and immediately moved to forestall any possible violence.[79] Within two months of Gandhi's death, Patel suffered a major heart attack; the timely action of his daughter, his secretary, and a nurse saved Patel's life. Speaking later, Patel attributed the attack to the "grief bottled up" due to Gandhi's death.[80]

Criticism arose from the media and other politicians that Patel's home ministry had failed to protect Gandhi. Emotionally exhausted, Patel tendered a letter of resignation, offering to leave the government. Patel's secretary persuaded him to withhold the letter, seeing it as fodder for Patel's political enemies and political conflict in India.[81] However, Nehru sent Patel a letter dismissing any question of personal differences or desire for Patel's ouster. He reminded Patel of their 30-year partnership in the independence struggle and asserted that after Gandhi's death, it was especially wrong for them to quarrel. Nehru, Rajagopalachari, and other Congressmen publicly defended Patel. Moved, Patel publicly endorsed Nehru's leadership and refuted any suggestion of discord, and dispelled any notion that he sought to be prime minister.[81] Though the two committed themselves to joint leadership and non-interference in Congress party affairs, they would criticise each other in matters of policy, clashing on the issues of Hyderabad's integration and UN mediation in Kashmir. Nehru declined Patel's counsel on sending assistance to Tibet after its 1950 invasion by the People's Republic of China and on ejecting the Portuguese from Goa by military force.[82] Nehru also tried to scuttle Patel's plan with regards to Hyderabad. During a meeting, according to the then civil servant MKK Nair in his book "With No Ill Feeling to Anybody", Nehru shouted and accused Patel of being a communalist.[citation needed] Patel also one on occasion called Nehru, a Maulana, for appeasing Muslims.[83]

When Nehru pressured Dr. Rajendra Prasad to decline a nomination to become the first President of India in 1950 in favour of Rajagopalachari, he angered the party, which felt Nehru was attempting to impose his will. Nehru sought Patel's help in winning the party over, but Patel declined, and Prasad was duly elected. Nehru opposed the 1950 Congress presidential candidate Purushottam Das Tandon, a conservative Hindu leader, endorsing Jivatram Kripalani instead and threatening to resign if Tandon was elected. Patel rejected Nehru's views and endorsed Tandon in Gujarat, where Kripalani received not one vote despite hailing from that state himself.[84] Patel believed Nehru had to understand that his will was not law with the Congress, but he personally discouraged Nehru from resigning after the latter felt that the party had no confidence in him.[85]

On 29 March 1949 authorities lost radio contact with a plane carrying Patel, his daughter Maniben, and the Maharaja of Patiala. Engine failure caused the pilot to make an emergency landing in a desert area in Rajasthan. With all passengers safe, Patel and others tracked down a nearby village and local officials. When Patel returned to Delhi, thousands of Congressmen gave him a resounding welcome. In Parliament, MPs gave a long standing ovation to Patel, stopping proceedings for half an hour.[86]

In his twilight years, Patel was honoured by members of Parliament. He was awarded honorary doctorates of law by Nagpur University, the University of Allahabad and Banaras Hindu University in November 1948, subsequently receiving honorary doctorates from Osmania University in February 1949 and from Punjab University in March 1949.[87][88] Previously, Patel had been featured on the cover page of the January 1947 issue of Time magazine.[89]

Death[edit]

Patel's health declined rapidly through the summer of 1950. He later began coughing blood, whereupon Maniben began limiting her meetings and working hours and arranged for a personalised medical staff to begin attending to Patel. The Chief Minister of West Bengaland doctor Bidhan Roy heard Patel make jokes about his impending end, and in a private meeting Patel frankly admitted to his ministerial colleague N. V. Gadgil that he was not going to live much longer. Patel's health worsened after 2 November, when he began losing consciousness frequently and was confined to his bed. He was flown to Bombay (now Mumbai) on 12 December on advice from Dr Roy, to recuperate as his condition was deemed critical.[90] Nehru, Rajagopalchari, Rajendra Prasad, and Menon all came to see him off at the airport in Delhi. Patel was extremely weak and had to be carried onto the aircraft in a chair. In Bombay, large crowds gathered at Santacruz Airport to greet him. To spare him from this stress, the aircraft landed at Juhu Aerodrome, where Chief Minister B. G. Kher and Morarji Desai were present to receive him with a car belonging to the Governor of Bombay that took Vallabhbhai to Birla House.[91][92]

After suffering a massive heart attack (his second), Patel died at 9:37 a.m. on 15 December 1950 at Birla House in Bombay.[93] In an unprecedented and unrepeated gesture, on the day after his death more than 1,500 officers of India's civil and police services congregated to mourn at Patel's residence in Delhi and pledged "complete loyalty and unremitting zeal" in India's service.[94] Numerous governments and world leaders sent messages of condolence upon Patel's death, including Trygve Lie, the Secretary-General of the United Nations, President Sukarno of Indonesia, Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan of Pakistan and Prime Minister Clement Attlee of the United Kingdom.[95]

In homage to Patel, the Indian government declared a week of national mourning.[96] Patel's cremation was planned at Girgaum Chowpatty, but this was changed to Sonapur (now Marine Lines) when his daughter conveyed that it was his wish to be cremated like a common man in the same place as his wife and brother were earlier cremated. His cremation in Sonapur in Bombay was attended by a crowd of one million including Prime Minister Nehru, Rajagopalachari, and President Rajendra Prasad.[92][97][98]

Reception[edit]

During his lifetime, Vallabhbhai Patel received criticism for an alleged bias against Muslims during the time of Partition. He was criticised by Maulana Azad and others for readily plumping for partition.[99] Guha says that, during the Partition, Nehru wanted the government to make the Muslims stay back and feel secure in India while Patel was inclined to place that responsibility on the individuals themselves. Patel also told Nehru that the minority also had to remove the doubts that were entertained about their loyalty based on their past association with the demand of Pakistan.[100] However, Patel successfully prevented attacks upon a train of Muslim refugees leaving India.[101] In September 1947 he was said to have had ten thousand Muslims sheltered safely in the Red Fort and had free kitchens opened for them during the communal violence.[102] Patel was also said to be more forgiving of Indian nationalism and harsher on Pakistan.[103] He exposed a riot plot, confiscated a large haul of weapons from the Delhi Jumma Masjid, and had a few plotters killed by the police, but his approach was said to have been harsh.[102]

Patel was also criticised by supporters of Subhas Chandra Bose for acting coercively to put down politicians not supportive of Gandhi.[104] Socialist politicians such as Jaya Prakash Narayan and Asoka Mehta criticised him for his personal proximity to Indian industrialists such as the Birla and Sarabhai families. It is said that Patel was friendly towards capitalists while Nehru believed in the state controlling the economy.[103] Also, Patel was more inclined to support the West in the emerging Cold War.[103]

Nehru and Patel[edit]

Some historians and admirers of Patel such as Rajendra Prasad, the first President of India and industrialist J. R. D. Tata have expressed the opinion that Patel would have made a better Prime Minister for India than Nehru.[105]These admirers and Nehru's critics cite Nehru's belated embrace of Patel's advice regarding the UN and Kashmir and the integration of Goa by military action and Nehru's rejection of Patel's advice on China.[106] Proponents of free enterprise cite the failings of Nehru's socialist policies as opposed to Patel's defence of property rights and his mentorship of what was to be later known as the Amul co-operative project.[107][108] However, A. G. Noorani, in comparing Nehru and Patel, writes that Nehru had a broader understanding of the world than Patel.[109]

Legacy[edit]

In his eulogy, delivered the day after Patel's death, Sir Girija Shankar Bajpai, the Secretary-General of the Ministry of External Affairs, paid tribute to "a great patriot, a great administrator and a great man. Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel was all three, a rare combination in any historic epoch and in any country."[87] Bajpai lauded Patel for his achievements as a patriot and as an administrator, notably his vital role in securing India's stability in the aftermath of Independence and Partition:

Among Patel's surviving family, Maniben Patel lived in a flat in Mumbai for the rest of her life following her father's death; she often led the work of the Sardar Patel Memorial Trust, which organises the prestigious annual Sardar Patel Memorial Lectures, and other charitable organisations. Dahyabhai Patel was a businessman who was elected to serve in the Lok Sabha (the lower house of the Indian Parliament) as an MP in the 1960s.[110]

For many decades after his death, there was a perceived lack of effort from the Government of India, the national media, and the Congress party regarding commemoration of Patel's life and work.[111] Patel was posthumously awarded the Bharat Ratna, India's highest civilian honour, in 1991.[112] It was announced in 2014 that his birthday, 31 October, would become an annual national celebration known as Rashtriya Ekta Diwas (National Unity Day).[113] Patel's legacy has been surprisingly adored by the RSS and BJP, against whom Patel had acted coercively, forcing them to stay away from communal politics after Gandhi's assassination.

Patel's family home in Karamsad is preserved in his memory.[114] The Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel National Memorial in Ahmedabad was established in 1980 at the Moti Shahi Mahal. It comprises a museum, a gallery of portraits and historical pictures, and a library containing important documents and books associated with Patel and his life. Amongst the exhibits are many of Patel's personal effects and relics from various periods of his personal and political life.[115]

Patel is the namesake of many public institutions in India. A major initiative to build dams, canals, and hydroelectric power plants in the Narmada river valley to provide a tri-state area with drinking water and electricity and to increase agricultural production was named the Sardar Sarovar. Patel is also the namesake of the Sardar Vallabhbhai National Institute of Technology in Surat, Sardar Patel University, Sardar Patel High School, and the Sardar Patel Vidyalaya, which are among the nation's premier institutions. India's national police training academy is also named after him.[116]

The international airport of Ahmedabad is named after him. Also the international cricket stadium of Ahmedabad (also known as the Motera Stadium) is named after him. A national cricket stadium in Navrangpura, Ahmedabad, used for national matches and events, is also named after him. The chief outer ring road encircling Ahmedabad is named S P Ring Road. The Gujarat government's institution for training government functionaries is named Sardar Patel Institute of Public Administration.[citation needed]

Rashtriya Ekta Diwas[edit]

Rashtriya Ekta Diwas (National Unity Day) was introduced by the Government of India and inaugurated by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2014. The intent is to pay tribute to Patel, who was instrumental in keeping India united. It is to be celebrated on 31 October every year as annual commemoration of the birthday of the Iron Man of India Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, one of the founding leaders of Republic of India. The official statement for Rashtriya Ekta Diwas by the Home Ministry of India cites that the National Unity Day "will provide an opportunity to re-affirm the inherent strength and resilience of our nation to withstand the actual and potential threats to the unity, integrity and security of our country."[117]

National Unity Day celebrates the birthday of Patel because, during his term as Home Minister of India, he is credited for the integration of over 550 independent princely states into India from 1947-49 by Independence Act (1947). He is known as the "Bismarck[a] of India".[118][119] The celebration is complemented with the speech of Prime Minister of India followed by the "Run for Unity".[120] The theme for 2016 celebrations was "Integration of India".[121]

Statue of unity[edit]

The Statue of Unity is an under construction monument dedicated to Indian independence movement leader Vallabhbhai Patel located in the Indian state of Gujarat. 182 metres (597feet) in height, it is to be located facing the Narmada Dam, 3.2 km away on the river island called Sadhu Bet near Vadodara in Gujarat. This statue is planned to be spread over 20,000 square meters of project area and will be surrounded by an artificial lake spread across 12km of area. It would be the world's tallest statue when completed,.[122] standing at a height of 182 metres (600ft) [123] This is getting inaugurated by India's Prime Minister Narendra Modi on 31 Oct. 2018.

Other institutions and monuments[edit]

- Sardar Patel Memorial Trust

- Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel National Memorial, Ahmedabad

- Sardar Sarovar Dam, Gujarat

- Sardar Vallabhbhai National Institute of Technology, Surat

- Sardar Patel University, Gujarat

- Sardar Patel University of Police, Security and Criminal Justice, Jodhpur

- Sardar Patel Institute of Technology, Vasad

- Sardar Patel Vidyalaya, New Delhi

- Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel National Police Academy, Hyderabad

- Sardar Patel College of Engineering, Mumbai

- Sardar Patel Institute of Technology, Mumbai

- Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Chowk in Katra Gulab Singh, Pratapgarh, Uttar Pradesh

- Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Institute of Technology, Vasad

- Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel International Airport, Ahmedabad

- Sardar Patel Stadium

- Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Stadium, Ahmedabad

- Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel University of Agriculture and Technology

- Vallabhbhai Patel Chest Institute

Bal Gangadhar Tilak

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)Bal Gangadhar Tilak  Bal Gangadhar Tilak

Bal Gangadhar TilakBorn 23 July 1856

Ratnagiri, Bombay State, British India (present-day Maharashtra, India)[1]Died 1 August 1920 (aged 64)

Bombay, British India (present-day Maharashtra, India)Occupation Author, politician, freedom fighter Political party Indian National Congress Movement Indian Independence movement Children Sridhar Balwant Tilak[2] Bal Gangadhar Tilak (or Lokmanya Tilak, pronunciation (help·info); 23 July 1856 – 1 August 1920), born as Keshav Gangadhar Tilak, was an Indian nationalist, teacher, lawyer and an independence activist. He was the first leader of the Indian Independence Movement. The British colonial authorities called him "The father of the Indian unrest." He was also conferred with the title of "Lokmanya", which means "accepted by the people (as their leader)".[3]Tilak was one of the first and strongest advocates of Swaraj ("self-rule") and a strong radical in Indian consciousness. He is known for his quote in Marathi: "Swarajya is my birthright and I shall have it!". He formed a close alliance with many Indian National Congress leaders including Bipin Chandra Pal, Lala Lajpat Rai, Aurobindo Ghose, V. O. Chidambaram Pillai and Muhammad Ali Jinnah.

pronunciation (help·info); 23 July 1856 – 1 August 1920), born as Keshav Gangadhar Tilak, was an Indian nationalist, teacher, lawyer and an independence activist. He was the first leader of the Indian Independence Movement. The British colonial authorities called him "The father of the Indian unrest." He was also conferred with the title of "Lokmanya", which means "accepted by the people (as their leader)".[3]Tilak was one of the first and strongest advocates of Swaraj ("self-rule") and a strong radical in Indian consciousness. He is known for his quote in Marathi: "Swarajya is my birthright and I shall have it!". He formed a close alliance with many Indian National Congress leaders including Bipin Chandra Pal, Lala Lajpat Rai, Aurobindo Ghose, V. O. Chidambaram Pillai and Muhammad Ali Jinnah.Contents

Early life[edit]

Tilak was born in a Marathi Chitpavan Brahmin family in Ratnagiri as Keshav Gangadhar Tilak, in the headquarters of the eponymous district of present-day Maharashtra (then British India) on 23 July 1856.[1] His ancestral village was Chikhali. His father, Gangadhar Tilak was a school teacher and a Sanskrit scholar who died when Tilak was sixteen. In 1871 Tilak was married to Tapibai (Née Bal) when he was sixteen, a few months before his father's death. After marriage, her name was changed to Satyabhamabai. He obtained his Bachelor of Arts in first class in Mathematics from Deccan College of Pune in 1877. He left his M.A. course of study midway to join the LL.B course instead, and in 1879 he obtained his LL.B degree from Government Law College .[4] After graduating, Tilak started teaching mathematics at a private school in Pune. Later, due to ideological differences with the colleagues in the new school, he withdrew and became a journalist. Tilak actively participated in public affairs. He stated: "Religion and practical life are not different.The real spirit is to make the country your family instead of working only for your own. The step beyond is to serve humanity and the next step is to serve God."[5]Inspired by Vishnushastri Chiplunkar, he co-founded the New English school for secondary education in 1880 with a few of his college friends, including Gopal Ganesh Agarkar, Mahadev Ballal Namjoshi. and Vishnushastri Chiplunkar. Their goal was to improve the quality of education for India's youth.The success of the school led them to set up the Deccan Education Society in 1884 to create a new system of education that taught young Indians nationalist ideas through an emphasis on Indian culture.[6] The Society established the Fergusson College in 1885 for post-secondary studies. Tilak taught mathematics at Fergusson College. In 1890, Tilak left the Deccan Education Society for more openly political work.[7] He began a mass movement towards independence by an emphasis on a religious and cultural revival.[8]Political career[edit]

Tilak had a long political career agitating for Indian autonomy from the British rule.{ Before Gandhi, he was the most widely known Indian political leader. Unlike his fellow Maharashtrian contemporary, Gokhale, Tilak was considered a radical Nationalist but a Social conservative. He was imprisoned on a number of occasions that included a long stint at Mandalay. At one stage in his political life he was called "the father of Indian unrest" by british author Sir Valentine Chirol.[9]Indian National Congress[edit]

Tilak joined the Indian National Congress in 1890.[citation needed] He opposed its moderate attitude, especially towards the fight for self-government. He was one of the most-eminent radicals at the time.[10] In fact, it was the Swadeshi movement of 1905-1907 that resulted in the split within the Indian National Congress into the Moderates and the Extremists[7]Despite being personally opposed to early marriage, Tilak was against the 1891 Age of Consent bill, seeing it as interference with Hinduism and a dangerous precedent.[citation needed] The act raised the age at which a girl could marry from 10 to 12 years.[citation needed]During late 1896, a bubonic plague spread from Bombay to Pune, and by January 1897, it reached epidemic proportions. British troops were brought in to deal with the emergency and harsh measures were employed including forced entry into private houses, examination of occupants, evacuation to hospitals and segregation camps, removing and destroying personal possessions, and preventing patients from entering or leaving the city. By the end of May, the epidemic was under control. They were widely regarded as acts of tyranny and oppression. Tilak took up this issue by publishing inflammatory articles in his paper Kesari (Kesari was written in Marathi, and "Maratha" was written in English), quoting the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad Gita, to say that no blame could be attached to anyone who killed an oppressor without any thought of reward. Following this, on 22 June 1897, Commissioner Rand and another British officer, Lt. Ayerst were shot and killed by the Chapekar brothers and their other associates. According to Barbara and Thomas R. Metcalf, Tilak "almost surely concealed the identities of the perpetrators".[11]:154 Tilak was charged with incitement to murder and sentenced to 18 months imprisonment. When he emerged from prison in present-day Mumbai, he was revered as a martyr and a national hero.[citation needed] He adopted a new slogan coined by his associate Kaka Baptista: "Swaraj (self-rule) is my birthright and I shall have it."[12]Following the Partition of Bengal, which was a strategy set out by Lord Curzon to weaken the nationalist movement, Tilak encouraged the Swadeshi movement and the Boycott movement.[13] The movement consisted of the boycott of foreign goods and also the social boycott of any Indian who used foreign goods. The Swadeshi movement consisted of the usage of natively produced goods. Once foreign goods were boycotted, there was a gap which had to be filled by the production of those goods in India itself. Tilak said that the Swadeshi and Boycott movements are two sides of the same coin.[citation needed]Tilak opposed the moderate views of Gopal Krishna Gokhale, and was supported by fellow Indian nationalists Bipin Chandra Pal in Bengal and Lala Lajpat Rai in Punjab. They were referred to as the "Lal-Bal-Pal triumvirate". In 1907, the annual session of the Congress Party was held at Surat, Gujarat. Trouble broke out over the selection of the new president of the Congress between the moderate and the radical sections of the party . The party split into the radicals faction, led by Tilak, Pal and Lajpat Rai, and the moderate faction. Nationalists like Aurobindo Ghose, V. O. Chidambaram Pillai were Tilak supporters.[10][14]Sedition Charges[edit]

During his lifetime among other political cases, Bal Gangadhar Tilak had been tried for Sedition Charges in three times by British India Government—in 1897,[15] 1909,[16] and 1916.[17] In 1897, Tilak was sentenced to 18 months in prison for preaching disaffection against the Raj. In 1909, he was again charged with sedition and intensifying racial animosity between Indians and the British. The Bombay lawyer Muhammad Ali Jinnah in Tilak's defence could not annul the evidence in Tilak's polemical articles and Tilak was sentenced to six years in prison in Burma.[7]Imprisonment in Mandalay[edit]

On 30 April 1908, two Bengali youths, Prafulla Chaki and Khudiram Bose, threw a bomb on a carriage at Muzzafarpur, to kill the Chief Presidency Magistrate Douglas Kingsford of Calcutta fame, but erroneously killed two women traveling in it. While Chaki committed suicide when caught, Bose was hanged. Tilak, in his paper Kesari, defended the revolutionaries and called for immediate Swaraj or self-rule. The Government swiftly charged him with sedition. At the conclusion of the trial, a special jury convicted him by 7:2 majority. The judge, Dinshaw D. Davar[18] gave him a six years jail sentence to be served in Mandalay, Burma and a fine of Rs 1,000. On being asked by the judge whether he had anything to say, Tilak said:In passing sentence, the judge indulged in some scathing strictures against Tilak's conduct. He threw off the judicial restraint which, to some extent, was observable in his charge to the jury. He condemned the articles as "seething with sedition", as preaching violence, speaking of murders with approval. "You hail the advent of the bomb in India as if something had come to India for its good. I say, such journalism is a curse to the country". Tilak was sent to Mandalay from 1908 to 1914.[19] While imprisoned, he continued to read and write, further developing his ideas on the Indian nationalist movement. While in the prison he wrote the Gita Rahasya. Many copies of which were sold, and the money was donated for the Indian Independence movement.[citation needed].Life after Mandalay[edit]

This section does not cite any sources. (September 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)Tilak developed diabetes during his sentence in Mandalay prison. This and the general ordeal of prison life had mellowed him at his release on 16 June 1914. When World War I started in August of that year, Tilak cabled the King-Emperor George V of his support and turned his oratory to find new recruits for war efforts. He welcomed The Indian Councils Act, popularly known as Minto-Morley Reforms, which had been passed by British Parliament in May 1909, terming it as "a marked increase of confidence between the Rulers and the Ruled". It was his conviction that acts of violence actually diminished, rather than hastening, the pace of political reforms. He was eager for reconciliation with Congress and had abandoned his demand for direct action and settled for agitations "strictly by constitutional means" – a line advocated by his rival Gokhale.Tilak tried to convince Mohandas Gandhi to leave the idea of Total non-violence ("Total Ahimsa") and try to get self-rule ("Swarajya") by all means.[citation needed]All India Home Rule League[edit]

Later, Tilak re-united with his fellow nationalists and re-joined the Indian National Congress in 1916. He also helped found the All India Home Rule League in 1916–18, with G. S. Khaparde and Annie Besant. After years of trying to reunite the moderate and radical factions, he gave up and focused on the Home Rule League, which sought self-rule. Tilak travelled from village to village for support from farmers and locals to join the movement towards self-rule.[19] Tilak was impressed by the Russian Revolution, and expressed his admiration for Vladimir Lenin.[20] The league had 1400 members in April 1916, and by 1917 membership had grown to approximately 32,000. Tilak started his Home Rule League in Maharashtra, Central Provinces, and Karnataka and Berar region. Besant's League was active in the rest part of India.[21]Tilak, progressed into a prominent nationalist after his close association with Indian nationalists following the partition of Bengal. When asked in Calcutta whether he envisioned a Maratha-type of government for independent India, Tilak replied that the Maratha-dominated governments of 17th and 18th centuries were outmoded in the 20th century, and he wanted a genuine federal system for Free India where every religion and race was an equal partner.[citation needed] He added that only such a form of government would be able to safeguard India's freedom. He was the first Congress leader to suggest that Hindi written in the Devanagari script be accepted as the sole national language of India.[22]Religio-Political Views[edit]

Tilak sought to unite the Indian population for mass political action throughout his life. For this to happen, he believed there needed to be a comprehensive justification for anti-British pro-Hindu activism. For this end, he sought justification in the supposed original principles of the Ramayana and the Bhagavad Gita. He named this call to activism karma-yoga or the yoga of action.[23] In his interpretation, the Bhagavad Gita reveals this principle in the conversation between Krishna and Arjuna when Krishna exhorts Arjuna to fight his enemies (which in this case included many members of his family) because it is his duty. In Tilaks opinion, the Bhagavad Gita provided a strong justification of activism. However, this conflicted with the mainstream exegesis of the text at the time which was predominated by renunciate views and the idea of acts purely for God. This was represented by the two mainstream views at the time by Ramanuja and Adi Shankara. To find support for this philosophy, Tilak wrote his own interpretations of the relevant passages of the Gita and backed his views using Jnanadeva's commentary on the Gita, Ramanuja's critical commentary and his own translation of the Gita.[24] His main battle was against the renunciate views of the time which conflicted with worldly activism. To fight this, he went to extents to reinterpret words such as karma, dharma, yoga as well as the concept of renunciation itself. Because he found his rationalization on Hindu religious symbols and lines, this alienated many non-Hindus such as the Muslims who began to ally with the British for support.Social views[edit]

Tilak was strongly opposed to liberal trends emerging in Pune such as women's rights and social reforms against untouchability.[25][26][27]Women's issues[edit]

Tilak vehemently opposed the establishment of the first Native girls High school (now called Huzurpaga) in Pune in 1885 and its curriculum using his newspapers, the Mahratta and Kesari.[26][28][29] Tilak was also opposed to intercaste marriage, particularly the match where an upper caste woman married a lower caste man.[29] In the case of Deshasthas, Chitpawans and Karhades, he encouraged these three Maharashtrian Brahmin groups to give up "caste exclusiveness" and intermarry.[30] Tilak officially opposed the age of consent bill which raised the age of marriage from ten to twelve for girls, however he was willing to sign a circular that increased age of marriage for girls to sixteen and twenty for boys. In his opinion, self-rule took precedence over any social reform.[31]Child bride Rukhmabai was married at the age of eleven but refused to go and live with her husband. The husband sued for restitution of conjugal rights, initially lost but appealed the decision. On 4 March 1887, Justice Farran, using interpretations of Hindu laws, ordered Rukhmabai to "go live with her husband or face six months of imprisonment". Tilak approved of this decision of the court and said that the court was following Hindu Dharmaśāstras. Rukhmabai responded that she would rather face imprisonment than obey the verdict. Her marriage was later dissolved by Queen Victoria. Later, she went on to receive her Doctor of Medicine degree from the London School of Medicine for Women.[32][33][34][35]In 1890, when an eleven year old Phulamani Bai died while having sexual intercourse with her much older husband, the Parsi social reformer Behramji Malabari supported the Age of Consent Act, 1891 to raise the age of a girl's eligibility for marriage. Tilak opposed the Bill and said that the Parsis as well as the English had no jurisdiction over the (Hindu) religious matters. He blamed the girl for having "defective female organs" and questioned how the husband could be "persecuted diabolically for doing a harmless act". He called the girl one of those "dangerous freaks of nature".[27]Tilak did not have a progressive view when it came to gender relations. He did not believe that Hindu women should get a modern education. Rather, he had a more conservative view, believing that women were meant to be homemakers who had to subordinate themselves to the needs of their husbands and children.[7]Untouchability[edit]

Tilak refused to sign a petition for the abolition of untouchability in 1918, two years before his death, although he had spoken against it earlier in a meeting.[25]Esteem for Swami Vivekananda[edit]

Tilak and Swami Vivekananda had great mutual respect and esteem for each other. They met accidentally while travelling by train in 1892 and Tilak had Vivekananda as a guest in his house. A person who was present there(Basukaka), heard that it was agreed between Vivekananda and Tilak that Tilak would work towards nationalism in the "political" arena , while Vivekananda would work for nationalism in the "religious" arena. When Vivekanada passed away at a young age , Tilak expressed great sorrow and paid tributes to him in the Kesari.[36][37][38][39] Tilak said about Vivekananda:Conflicts with Shahu over caste issues[edit]

Shahu had several conflicts with Tilak as the latter agreed with the Brahmin decision of puranic rituals for the Marathas that were intended for Shudras. Tilak even suggested that the Marathas should be "content" with the Shudra status assigned to them by the Brahmins. Tilak's newspapers as well as the press in Kolhapur criticized Shahu for his caste prejudice and his unreasoned hostility towards Brahmins. These included serious allegations such as sexual assaults by Shahu against four Brahmin women. An englishwoman named lady Minto was petitioned to help them. The agent of Shahu had blamed these allegations on the "troublesome brahmins". Tilak and another Brahmin suffered from the confiscation of estates by Shahu, the first during a quarrel between Shahu and the Shankaracharya of Sankareshwar and later in another issue.[41][42]Social contributions and legacy[edit]