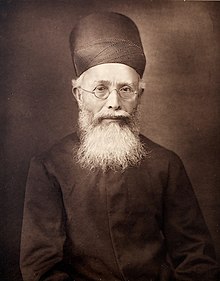

Lala Lajpat Rai

| Lala Lajpat Rai | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 28 January 1865 Dhudike, Punjab, British India |

| Died | 17 November 1928 (aged 63) Lahore, Punjab, British India |

| Occupation | Author, politician, freedom fighter |

| Political party | Indian National Congress, Hindu Mahasabha |

| Movement | Indian Independence movement |

Lala Lajpat Rai  pronunciation (help·info), (28 January 1865 – 17 November 1928) was an Indian freedom fighter. He played a pivotal role in the Indian Independence movement. He was popularly known as Punjab Kesari. He was one third of the Lal Bal Pal triumvirate.[1] He was also associated with activities of Punjab National Bank and Lakshmi Insurance Company in their early stages in 1894

pronunciation (help·info), (28 January 1865 – 17 November 1928) was an Indian freedom fighter. He played a pivotal role in the Indian Independence movement. He was popularly known as Punjab Kesari. He was one third of the Lal Bal Pal triumvirate.[1] He was also associated with activities of Punjab National Bank and Lakshmi Insurance Company in their early stages in 1894

Contents

Early life[edit]

Lajpat Rai was born on 28 January 1865 in a Hindu Aggarwal family,[2] as a son of Urdu and Persian government school teacher Munshi Radha Krishan Agrawal and his wife Gulab Devi Agrawal, in Dhudike (now in Moga district, Punjab).[3][4][5] In 1877, he was married to Radha Devi Agrawal, with whom had two sons, Amrit Rai Agrawal and Pyarelal Agrawal, and a daughter, Parvati Agrawal.

In the late 1870s, his father was transferred to Rewari, where he had his initial education in Government Higher Secondary School, Rewari (now in Haryana, previously in joint Punjab), where his father was posted as an Urduteacher. During his early life, Rai's liberal views and belief in Hinduism were shaped by his father and deeply religious mother respectively, which he successfully applied to create a career of reforming the religion and Indian policy through politics and journalistic writing.[6] In 1880, Lajpat Rai joined Government College at Lahore to study Law, where he came in contact with patriots and future freedom fighters, such as Lala Hans Raj and Pandit Guru Dutt. While studying at Lahore he was influenced by the Hindu reformist movement of Swami Dayanand Sarasvati, became a member of existing Arya Samaj Lahore (founded 1877) and founder editor of Lahore-based Arya Gazette.[7] When studying law, he became a bigger believer in the idea that Hinduism, above nationality, was the pivotal point upon which an Indian lifestyle must be based. He believed, Hinduism, led to practices of peace to humanity, and the idea that when nationalist ideas were added to this peaceful belief system, a secular nation could be formed. His involvement with Hindu Mahasabha leaders gathered criticism from the Naujawan Bharat Sabha as the Mahasabhas were non-secular, which did not conform with the system laid out by the Indian National Congress.[8] This focus on Hindu practices in the subcontinent would ultimately lead him to the continuation of peaceful movements to create successful demonstrations for Indian independence.[7]

In 1884, his father was transferred to Rohtak and Rai came along after the completion of his studies at Lahore. In 1886, he moved to Hisar where his father was transferred, and started to practice law and became founding member of Bar council of Hisar along with Babu Churamani. Since childhood he also had a desire to serve his country and therefore took a pledge to free it from foreign rule, in the same year he also founded the Hisar district branch of the Indian National Congress and reformist Arya Samaj with Babu Churamani (lawyer), three Tayal brothers (Chandu Lal Tayal, Hari Lal Tayal and Balmokand Tayal), Dr. Ramji Lal Hooda, Dr. Dhani Ram, arya samaji Pandit Murari Lal, Seth Chhaju Ram Jat (founder of Jat School, Hisar) and Dev Raj Sandhir. In 1888 and again in 1889, he had the honor of being one of the four delegates from Hisar to attend the annual session of the Congress at Allahabad, along with Babu Churamani, Lala Chhabil Das and Seth Gauri Shankar. In 1892, he moved to Lahore to practice before the Lahore High Court. To shape the political policy of India to gain independence, he also practiced journalism and was a regular contributor to several newspapers including The Tribune. In 1886, he helped Mahatma Hansraj establish the nationalistic Dayananda Anglo-Vedic School, Lahore which was converted to Islamia College (Lahore)after 1947 partition of India.

In college where he studied law, he came into contact with other future freedom fighters, such as Lala Hans Raj and Pandit Guru Dutt. Then his family went to Hissar where he then practiced law. Then to Lahore to practice in front of the high court in 1892.[9]

In 1914, he quit law practice to dedicate himself to the freedom of India and went to Britain in 1914 and then to the United States in 1917. In October 1917, he founded the Indian Home Rule League of America in New York. He stayed in the United States from 1917 to 1920.

Nationalism[edit]

After joining the Indian National Congress and taking part in political agitation in Punjab, Lala Lajpat Rai was deported to Mandalay, Burma (now Myanmar), without trial in May 1907. In November, however, he was allowed to return when the viceroy, Lord Minto, decided that there was insufficient evidence to hold him for subversion. Lajpat Rai's supporters attempted to secure his election to the presidency of the party session at Surat in December 1907, but he did not succeed.

Graduates of the National College, which he founded inside the Bradlaugh Hall at Lahore as an alternative to British institutions, included Bhagat Singh.[10] He was elected President of the Indian National Congress in the Calcutta Special Session of 1920.[11] In 1921, he founded Servants of the People Society, a non-profit welfare organisation, in Lahore, which shifted its base to Delhi after partition, and has branches in many parts of India.[12]

Travel to America[edit]

Lajpat Rai travelled to the US in 1907, and then returned during World War I. He toured Sikh communities along the US West Coast; visited Tuskegee University in Alabama; and met with workers in the Philippines. His travelogue, The United States of America (1916), details these travels and features extensive quotations from leading African American intellectuals, including W.E.B. Du Bois and Fredrick Douglass. While in America he had founded the Indian Home Rule League in New York and a monthly journal Young India and Hindustan Information Services Association. He had petitioned the Foreign affiars committee of Senate of American Parliament giving a vivid picture of maladministration of British Raj in India, the aspirations of the people of India for freedom amongst many other points strongly seeking the moral support of the international community for the attainment of independence of India. The 32 page petition which was prepared overnight was discussed in the U.S. Senate during October 1917. [13]

Demand for separate state for Muslims[edit]

He controversially demanded "a clear partition of India into a Muslim India and Hindu State India" in The Tribune on 14 December 1923.[14][15]

Protests against Simon Commission[edit]

In 1928, the British government set up the Commission, headed by Sir John Simon, to report on the political situation in India. The Indian political parties boycotted the Commission, because it did not include a single Indian in its membership, and it met with country-wide protests. When the Commission visited Lahore on 30 October 1928, Lajpat Rai led silent march in protest against it. The superintendent of police, James A. Scott, ordered the police to lathi (baton) charge the protesters and personally assaulted Rai.[16] Despite being injured, Rai subsequently addressed the crowd and said, "I declare that the blows struck at me today will be the last nails in the coffin of British rule in India".[17]

Death[edit]

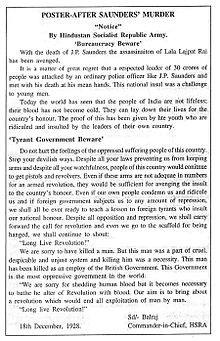

He did not fully recover from his injuries and died on 17 November 1928 of a heart attack. Doctors thought that Scott's blows had hastened his death.[16] However, when the matter was raised in the British Parliament, the British Government denied any role in Rai's death.[18] Although Bhagat Singh did not witness the event,[19] he vowed to take revenge,[18] and joined other revolutionaries, Shivaram Rajguru, Sukhdev Thapar and Chandrashekhar Azad, in a plot to kill Scott.[20] However, in a case of mistaken identity, Bhagat Singh was signalled to shoot on the appearance of John P. Saunders, an Assistant Superintendent of Police. He was shot by Rajguru and Bhagat Singh while leaving the District Police Headquarters in Lahore on 17 December 1928.[21] Chanan Singh, a Head Constable who was chasing them, was fatally injured by Azad's covering fire.[22]

This case of mistaken identity did not stop Bhagat Singh and his fellow-members of the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association from claiming that retribution had been exacted.[20]

Legacy[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification.(December 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

Movements and institutes founded by Lala Lajpat Rai[edit]

Lajpat Rai was a heavyweight veteran leader of the Indian Nationalist Movement, Indian independence movement, Hindu reform movements and Arya Samaj, who inspired young men of his generation and kindled latent spirit of patriotism in their hearts with journalistic writings and lead-by-example activism. Young men, such as Chandrasekhar Azad and Bhagat Singh, were driven to sacrifice their lives for the freedom of their Motherland following Rai's example.

In late 19th and early 20th century Lala Lajpat Rai himself was founder of many organisations, including Arya Gazaette are Lahore, Hisar congress, Hisar Arya Samaj, Hisar Bar Council, national DAV managing Committee. Lala Lajpat Rai was also head of the "Lakshmi Insurance Company," and commissioned the Lakshmi Building in Karachi, which still bears a plaque in remembrance of him. Lakhsmi Insurance Company was merged with Life Insurance Corporation of India when en masse nationalisation of Life Insurance business happened during 1956.

In 1927, Lajpat Rai established a trust in her memory to build and run a tuberculosis hospital for women, reportedly at the location where his mother, Gulab Devi, had died of tuberculosis in Lahore.[23] This became known as the Gulab Devi Chest Hospital and opened on 17 July 1934. Now the Gulab Devi Memorial hospital is one of the biggest hospital of present Pakistan which services over 2000 patients at a time as in patients.

Monuments and institutes founded in memory of Lala Lajpat Rai[edit]

Erected in the early 20th century, a statue of Lajpat Rai at Lahore, was later moved central square in Shimla after the partition of India. In 1959, the Lala Lajpat Rai trust was formed on the eve of his Centenary Birth Celebration by a group of Punjabi philanthropists (including R.P Gupta and B.M Grover) who have settled and prospered in the Indian State of Maharashtra, which runs the Lala Lajpatrai College of Commerce and Economics in Mumbai. Lala Lajpat Rai Memorial Medical College, Meerut is named after him.[24] In 1998, Lala Lajpat Rai Institute of Engineering and Technology, Moga was named after him. In 2010, the Government of Haryana set up the Lala Lajpat Rai University of Veterinary & Animal Sciences at in Hisar in his memory.

Lajpat Nagar and Lala Lajpat Rai square with is statue in Hisar;[25] Lajpat Nagar and Lajpat Nagar Central Market in New Delhi,Lala Lajpat Rai memorial park in Lajpat Nagar, Lajpat Rai Market in Chandani Chowk, Delhi; Lala Lajpat Rai Hall of Residence at Indian Institutes of Technology (IIT) in Kanpur and Kharagpur; Lala Lajpat Rai Hospital in Kanpur; the bus terminus, several institutes, schools and libraries in his hometown of Jagraon are named in his honor. Further, there are several roads named after him in numerous metropolis and other towns of India.

Works[edit]

Along with founding Arya Gazaette as its editor, he regularly contributed to several major Hindi, Punjabi, English and Urdu newspapers and magazines. He also authored the following published books.

- The Story of My Deportation, 1908.

- Arya Samaj, 1915.

- The United States of America: A Hindu’s Impression, 1916.

- Unhappy India, 1928.

- England's Debt to India, 1917.

- Autobiographical Writings

- Young India: An Interpretation and a History of the Nationalist Movement from Within. New York: B.W. Huebsch, 1916. This book was written shortly after World War I broke out in Europe. Lajpat Rai was traveling in the United States at the time of Franz Ferdinand's assassination.[26] Rai wrote the book to exclaim his people's desire to help the British, who had been ruling in India since the mid-1700s, fight against the Germans. While the book makes the Indian people sound good, saying that they were rushing in masses to volunteer for war, one must take what Rai says with a grain of salt.[26] Rai is trying to gain American support in India against British colonialism, and the Indian people would look bad in the American public's, as well as government's, eyes if they were not willing to fight for the greater good, even on the side of Britain. Rai also makes the point to emphasize that the Indian people do not want to engage in a military conflict with Britain.[27] In Young India, Rai makes many parallels to the American fight for independence against the British, such as their common enemy (the British), their wish for self-sovereignty, and the right to bear arms as an independent nation. Rai uses Young India to convey his idea of an independent India, free from the viceroys and rule of the English Parliament. Rai wishes to have complete sovereignty from all foreign rule, but he needs to gain the support of America, his only true hope for an ally against Britain. Young India gives a first-hand account of one of the primary freedom fighters in India in the early 1900s. Rai was one of the most well-known leaders of the Nationalist, as well as Independence, Movement in India. By writing an account outlining the history of India, showing that the Indian people are better than the stereotype given by the West, willing and able to govern themselves, and attempting to gain American support against the Colonial British, Rai allows his readers to understand what is actually happening in India and why India should become an independent nation.

- The Collected Works of Lala Lajpat Rai, Volume 1 to Volume 15, edited by B.R. Nanda.

- He also wrote the biographies of Italian revolutionaries Mazzini and Garibaldi

References[edit]

- ^ Ashalatha, A.; Koropath, Pradeep; Nambarathil, Saritha (2009). "Chapter 6 – Indian National Movement". Social Science: Standard VIII Part 1 (PDF). Government of Kerala • Department of Education. State Council of Educational Research and Training (SCERT). p. 72. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- ^ Ganda Singh, ed. (1978). Deportation of Lala Lajpat Rai and Sardar Ajit Singh. Punjabi University. p. iii. OCLC 641497600.

- ^ Kathryn Tidrick (2006) Gandhi: a political and spiritual lifeI.B.Tauris ISBN 978-1-84511-166-3 pp. 113–114

- ^ Kenneth W. Jones (1976) Arya dharm: Hindu consciousness in 19th-century Punjab University of California Press ISBN 9788173047091 p.52

- ^ Purushottam Nagar (1977) Lala Lajpat Rai: the man and his ideas Manohar Book Service p.161

- ^ Lala Lajpat Rai. Encyclopædia Britannica. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/328063/Lala-Lajpat-Rai

- ^ a b "Lala Lajpat Rai". Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ^ S. K. Mittal and Irfan Habib. "Towards Independence and Socialist Republic: Naujawan Bharat Sabha”. Social Scientist Vol. 8 2, 1979.

- ^ http://www.culturalindia.net/leaders/lala-lajpat-rai.html

- ^ "Bradlaugh Hall's demise". Pakistan Today. 17 April 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Lala Lajpat Raiwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Head Office". Servants of the People Society. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ Raghunath Rai. History. VK Publications. p. 187. ISBN 81-87139-69-2.

- ^ http://www.frontline.in/static/html/fl1826/18260810.htm

- ^ http://www.thehindu.com/todays-paper/tp-features/tp-bookreview/politics-of-partition/article604519.ece

- ^ a b Rai, Raghunath (2006). History For Class 12: Cbse. India. VK Publications. p. 187. ISBN 978-81-87139-69-0.

- ^ Friend, Corinne (Fall 1977). "Yashpal: Fighter for Freedom – Writer for Justice". Journal of South Asian Literature. 13 (1): 65–90. JSTOR 40873491. (subscription required)

- ^ a b Rana, Bhawan Singh (2005). Bhagat Singh. Diamond Pocket Books. p. 36. ISBN 978-81-288-0827-2.

- ^ Singh, Bhagat; Hooja, Bhupendra (2007). The Jail Notebook and Other Writings. LeftWord Books. p. 16. ISBN 978-81-87496-72-4.

- ^ a b Gupta, Amit Kumar (Sep–Oct 1997). "Defying Death: Nationalist Revolutionism in India, 1897–1938". Social Scientist. 25 (9/10): 3–27. JSTOR 3517678.

- ^ Nayar, Kuldip (2000). The martyr: Bhagat Singh experiments in revolution. Har-Anand Publications. p. 39. ISBN 978-81-241-0700-3.

- ^ Rana, Bhawan Singh (2005). Chandra Shekhar Azad (An Immortal Revolutionary of India). Diamond Pocket Books. p. 65. ISBN 978-81-288-0816-6.

- ^ "Gulab Devi Chest Hospital". Archived from the original on 15 October 2011. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- ^ "Lala Lajpat Rai Memorial Medical College’s maladies: Meagre budget, vacant posts ", Hindustan Times, 8 September 2017.

- ^ Tributes paid at Lala Lajpat Rai Square and Statute at Hisar, DNA News.

- ^ a b Rai, Lala Lajpat (1916). Young India. GoogleBooks. Huebsch. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ^ Hope, Ashley Guy (1968). America and Swaraj: The U.S. Role in Indian Independence. Washington, D.C.: Public Affairs Press.

Bhagat Singh

Bhagat Singh  Bhagat Singh in 1929

Bhagat Singh in 1929Born 1907[a]

Banga, Punjab, British India

(now in Punjab, Pakistan)Died 23 March 1931 (aged 23)

Lahore, Punjab, British India

(now in Punjab, Pakistan)Organization Naujawan Bharat Sabha

Hindustan Socialist Republican Association

Kirti Kisan PartyMovement Indian Independence movement Bhagat Singh (Punjabi pronunciation: [pə̀ɡət sɪ́ŋɡ] ( listen) 1907[a] – 23 March 1931) was an Indian nationalist considered to be one of the most influential revolutionaries of the Indian independence movement. He is often referred to as Shaheed Bhagat Singh, the word "Shaheed" meaning "martyr" in a number of Indian languages.In December 1928, Bhagat Singh and an associate, Shivaram Rajguru, fatally shot a 21-year-old British police officer, John Saunders, in Lahore, British India, mistaking Saunders, who was still on probation, for the British police superintendent, James Scott, whom they had intended to assassinate. They believed Scott was responsible for the death of popular Indian nationalist leader Lala Lajpat Rai, by having ordered a lathi charge in which Rai was injured, and, two weeks after which, died of a heart attack. Saunders was felled by a single shot from Rajguru, a marksman. He was then shot several times by Singh, the postmortem report showing eight bullet wounds. Another associate of Singh, Chandra Shekhar Azad, shot dead an Indian police constable, Chanan Singh, who attempted to pursue Singh and Rajguru as they fled.After escaping, Singh and his associates, using pseudonyms, publicly owned to avenging Lajpat Rai's death, putting up prepared posters, which, however, they had altered to show Saunders as their intended target. Singh was thereafter on the run for many months, and no convictions resulted at the time. Surfacing again in April 1929, he and another associate, Batukeshwar Dutt, exploded two improvised bombs inside the Central Legislative Assembly in Delhi. They showered leaflets from the gallery on the legislators below, shouted slogans, and then allowed the authorities to arrest them. The arrest, and the resulting publicity, had the effect of bringing to light Singh's complicity in the John Saunders case. Awaiting trial, Singh gained much public sympathy after he joined fellow defendant Jatin Das in a hunger strike, demanding better prison conditions for Indian prisoners, and ending in Das's death from starvation in September 1929. Singh was convicted and hanged in March 1931, aged 23.Bhagat Singh became a popular folk hero after his death. In still later years, Singh, an atheist and socialist in life, won admirers in India from among a political spectrum that included both Communists and right-wing Hindu nationalists. Although many of Singh's associates, as well as many Indian anti-colonial revolutionaries, were also involved in daring acts, and were either executed or died violent deaths, few came to be lionised in popular art and literature to the same extent as Singh.

listen) 1907[a] – 23 March 1931) was an Indian nationalist considered to be one of the most influential revolutionaries of the Indian independence movement. He is often referred to as Shaheed Bhagat Singh, the word "Shaheed" meaning "martyr" in a number of Indian languages.In December 1928, Bhagat Singh and an associate, Shivaram Rajguru, fatally shot a 21-year-old British police officer, John Saunders, in Lahore, British India, mistaking Saunders, who was still on probation, for the British police superintendent, James Scott, whom they had intended to assassinate. They believed Scott was responsible for the death of popular Indian nationalist leader Lala Lajpat Rai, by having ordered a lathi charge in which Rai was injured, and, two weeks after which, died of a heart attack. Saunders was felled by a single shot from Rajguru, a marksman. He was then shot several times by Singh, the postmortem report showing eight bullet wounds. Another associate of Singh, Chandra Shekhar Azad, shot dead an Indian police constable, Chanan Singh, who attempted to pursue Singh and Rajguru as they fled.After escaping, Singh and his associates, using pseudonyms, publicly owned to avenging Lajpat Rai's death, putting up prepared posters, which, however, they had altered to show Saunders as their intended target. Singh was thereafter on the run for many months, and no convictions resulted at the time. Surfacing again in April 1929, he and another associate, Batukeshwar Dutt, exploded two improvised bombs inside the Central Legislative Assembly in Delhi. They showered leaflets from the gallery on the legislators below, shouted slogans, and then allowed the authorities to arrest them. The arrest, and the resulting publicity, had the effect of bringing to light Singh's complicity in the John Saunders case. Awaiting trial, Singh gained much public sympathy after he joined fellow defendant Jatin Das in a hunger strike, demanding better prison conditions for Indian prisoners, and ending in Das's death from starvation in September 1929. Singh was convicted and hanged in March 1931, aged 23.Bhagat Singh became a popular folk hero after his death. In still later years, Singh, an atheist and socialist in life, won admirers in India from among a political spectrum that included both Communists and right-wing Hindu nationalists. Although many of Singh's associates, as well as many Indian anti-colonial revolutionaries, were also involved in daring acts, and were either executed or died violent deaths, few came to be lionised in popular art and literature to the same extent as Singh.Early life

Bhagat Singh, a Sandhu Jat,[4] was born in 1907[a] to Kishan Singh and Vidyavati at Chak No. 105 GB, Banga village, Jaranwala Tehsil in the Lyallpur district of the Punjab Province of British India. His birth coincided with the release of his father and two uncles, Ajit Singh and Swaran Singh, from jail.[5] His family members were Sikhs; some had been active in Indian Independence movements, others had served in Maharaja Ranjit Singh's army. His ancestral village was Khatkar Kalan, near the town of Banga, India in Nawanshahr district (now renamed Shaheed Bhagat Singh Nagar) of the Punjab.[6]His family was politically active.[7] His grandfather, Arjun Singh followed Swami Dayananda Saraswati's Hindu reformist movement, Arya Samaj, which had a considerable influence on Bhagat.[6] His father and uncles were members of the Ghadar Party, led by Kartar Singh Sarabha and Har Dayal. Ajit Singh was forced into exile due to pending court cases against him while Swaran Singh died at home in Lahore in 1910 following his release from jail.[8][b]Unlike many Sikhs of his age, Singh did not attend the Khalsa High School in Lahore. His grandfather did not approve of the school officials' loyalty to the British government.[10] He was enrolled instead in the Dayanand Anglo-Vedic High School, an Arya Samaji institution.[11]In 1919, when he was 12 years old, Singh visited the site of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre hours after thousands of unarmed people gathered at a public meeting had been killed.[5] When he was 14 years old, he was among those in his village who welcomed protesters against the killing of a large number of unarmed people at Gurudwara Nankana Sahib on 20 February 1921.[12] Singh became disillusioned with Mahatma Gandhi's philosophy of non-violence after he called off the non-co-operation movement. Gandhi's decision followed the violent murders of policemen by villagers who were reacting to the police killing three villagers in the 1922 Chauri Chaura incident. Singh joined the Young Revolutionary Movement and began to advocate for the violent overthrow of the British Government in India.[13]In 1923, Singh joined the National College in Lahore,[c] where he also participated in extra-curricular activities like the dramatics society. In 1923, he won an essay competition set by the Punjab Hindi Sahitya Sammelan, writing on the problems in the Punjab.[11] Inspired by the Young Italy movement of Giuseppe Mazzini,[7] he founded the Indian socialist youth organisation Naujawan Bharat Sabha in March 1926.[15] He also joined the Hindustan Republican Association,[16] which had prominent leaders, such as Chandrashekhar Azad, Ram Prasad Bismil and Shahid Ashfaqallah Khan.[17] A year later, to avoid an arranged marriage, Singh ran away to Cawnpore.[11] In a letter he left behind, he said:Police became concerned with Singh's influence on youths and arrested him in May 1927 on the pretext that he had been involved in a bombing that had taken place in Lahore in October 1926. He was released on a surety of Rs. 60,000 five weeks after his arrest.[18] He wrote for, and edited, Urdu and Punjabi newspapers, published in Amritsar[19] and also contributed to low-priced pamphlets published by the Naujawan Bharat Sabha that excoriated the British.[20] He also wrote for Kirti, the journal of the Kirti Kisan Party ("Workers and Peasants Party") and briefly for the Veer Arjun newspaper, published in Delhi.[15][d] He often used pseudonyms, including names such as Balwant, Ranjit and Vidhrohi.[21]Revolutionary activities

Lala Lajpat Rai's death and killing of Saunders

In 1928, the British government set up the Simon Commission to report on the political situation in India. Some Indian political parties boycotted the Commission because there were no Indians in its membership,[e] and there were protests across the country. When the Commission visited Lahore on 30 October 1928, Lala Lajpat Rai led a march in protest against it. Police attempts to disperse the large crowd resulted in violence. The superintendent of police, James A. Scott, ordered the police to lathi charge (use batons against) the protesters and personally assaulted Rai, who was injured. Rai died of a heart attack on 17 November 1928. Doctors thought that his death might have been hastened by the injuries he had received. When the matter was raised in the Parliament of the United Kingdom, the British Government denied any role in Rai's death.[23][24][25]Bhagat was a prominent member of the HRA and was probably responsible, in large part, for its change of name to HSRA in 1928.[7] The HSRA vowed to avenge Rai's death.[18] Singh conspired with revolutionaries like Shivaram Rajguru, Sukhdev Thapar, and Chandrashekhar Azad to kill Scott.[15] However, in a case of mistaken identity, the plotters shot John P. Saunders, an Assistant Superintendent of Police, as he was leaving the District Police Headquarters in Lahore on 17 December 1928.[26]Contemporary reaction to the killing differs substantially from the adulation that later surfaced. The Naujawan Bharat Sabha, which had organised the Lahore protest march along with the HSRA, found that attendance at its subsequent public meetings dropped sharply. Politicians, activists, and newspapers, including The People, which Rai had founded in 1925, stressed that non-co-operation was preferable to violence.[22] The murder was condemned as a retrograde action by Mahatma Gandhi, the Congress leader, but Jawaharlal Nehru later wrote that:Escape

After killing Saunders, the group escaped through the D.A.V. College entrance, across the road from the District Police Headquarters. Chanan Singh, a Head Constable who was chasing them, was fatally injured by Chandrashekhar Azad's covering fire.[28] They then fled on bicycles to pre-arranged safe houses. The police launched a massive search operation to catch them, blocking all entrances and exits to and from the city; the CID kept a watch on all young men leaving Lahore. The fugitives hid for the next two days. On 19 December 1928, Sukhdev called on Durgawati Devi, sometimes known as Durga Bhabhi, wife of another HSRA member, Bhagwati Charan Vohra, for help, which she agreed to provide. They decided to catch the train departing from Lahore to Bathinda en route to Howrah (Calcutta) early the next morning.[29]Singh and Rajguru, both carrying loaded revolvers, left the house early the next day.[29] Dressed in western attire (Bhagat Singh cut his hair, shaved his beard and wore a hat over cropped hair), and carrying Devi's sleeping child, Singh and Devi passed as a young couple, while Rajguru carried their luggage as their servant. At the station, Singh managed to conceal his identity while buying tickets, and the three boarded the train heading to Cawnpore (now Kanpur). There they boarded a train for Lucknow since the CID at Howrah railway station usually scrutinised passengers on the direct train from Lahore.[29] At Lucknow, Rajguru left separately for Benares while Singh, Devi and the infant went to Howrah, with all except Singh returning to Lahore a few days later.[30][29]1929 Assembly incident

For some time, Singh had been exploiting the power of drama as a means to inspire the revolt against the British, purchasing a magic lantern to show slides that enlivened his talks about revolutionaries such as Ram Prasad Bismil who had died as a result of the Kakori conspiracy. In 1929, he proposed a dramatic act to the HSRA intended to gain massive publicity for their aims.[20] Influenced by Auguste Vaillant, a French anarchist who had bombed the Chamber of Deputies in Paris,[31] Singh's plan was to explode a bomb inside the Central Legislative Assembly. The nominal intention was to protest against the Public Safety Bill, and the Trade Dispute Act, which had been rejected by the Assembly but were being enacted by the Viceroy using his special powers; the actual intention was for the perpetrators to allow themselves to be arrested so that they could use court appearances as a stage to publicise their cause.[21]The HSRA leadership was initially opposed to Bhagat's participation in the bombing because they were certain that his prior involvement in the Saunders shooting meant that his arrest would ultimately result in his execution. However, they eventually decided that he was their most suitable candidate. On 8 April 1929, Singh, accompanied by Batukeshwar Dutt, threw two bombs into the Assembly chamber from its public gallery while it was in session.[32] The bombs had been designed not to kill,[22] but some members, including George Ernest Schuster, the finance member of the Viceroy's Executive Council, were injured.[33] The smoke from the bombs filled the Assembly so that Singh and Dutt could probably have escaped in the confusion had they wished. Instead, they stayed shouting the slogan "Inquilab Zindabad!" ("Long Live the Revolution") and threw leaflets. The two men were arrested and subsequently moved through a series of jails in Delhi.[34]Assembly case trial

According to Neeti Nair, associate professor of history, "public criticism of this terrorist action was unequivocal."[22] Gandhi, once again, issued strong words of disapproval of their deed.[27] Nonetheless, the jailed Bhagat was reported to be elated, and referred to the subsequent legal proceedings as a "drama".[34] Singh and Dutt eventually responded to the criticism by writing the Assembly Bomb Statement:The trial began in the first week of June, following a preliminary hearing in May. On 12 June, both men were sentenced to life imprisonment for: "causing explosions of a nature likely to endanger life, unlawfully and maliciously."[34][35] Dutt had been defended by Asaf Ali, while Singh defended himself.[36] Doubts have been raised about the accuracy of testimony offered at the trial. One key discrepancy concerns the automatic pistol that Singh had been carrying when he was arrested. Some witnesses said that he had fired two or three shots while the police sergeant who arrested him testified that the gun was pointed downward when he took it from him and that Singh "was playing with it."[37] According to the India Law Journal, which believes that the prosecution witnesses were coached, these accounts were incorrect and Singh had turned over the pistol himself.[38] Singh was given a life sentence.[39]Capture

In 1929, the HSRA had set up bomb factories in Lahore and Saharanpur. On 15 April 1929, the Lahore bomb factory was discovered by the police, leading to the arrest of other members of HSRA, including Sukhdev, Kishori Lal, and Jai Gopal. Not long after this, the Saharanpur factory was also raided and some of the conspirators became informants. With the new information available, the police were able to connect the three strands of the Saunders murder, Assembly bombing, and bomb manufacture.[40] Singh, Sukhdev, Rajguru, and 21 others were charged with the Saunders murder.[41]Hunger strike and Lahore conspiracy case

Singh was re-arrested for murdering Saunders and Chanan Singh based on substantial evidence against him, including statements by his associates, Hans Raj Vohra and Jai Gopal.[38] His life sentence in the Assembly Bomb case was deferred until the Saunders case was decided.[39] He was sent to Central Jail Mianwali from the Delhi jail.[36] There he witnessed discrimination between European and Indian prisoners. He considered himself, along with others, to be a political prisoner. He noted that he had received an enhanced diet at Delhi which was not being provided at Mianwali. He led other Indian, self-identified political prisoners he felt were being treated as common criminals in a hunger strike. They demanded equality in food standards, clothing, toiletries, and other hygienic necessities, as well as access to books and a daily newspaper. They argued that they should not be forced to do manual labour or any undignified work in the jail.[42][22]The hunger strike inspired a rise in public support for Singh and his colleagues from around June 1929. The Tribune newspaper was particularly prominent in this movement and reported on mass meetings in places such as Lahore and Amritsar. The government had to apply Section 144 of the criminal code in an attempt to limit gatherings.[22]Jawaharlal Nehru met Singh and the other strikers in Mianwali jail. After the meeting, he stated:Muhammad Ali Jinnah spoke in support of the strikers in the Assembly, saying:The government tried to break the strike by placing different food items in the prison cells to test the prisoners' resolve. Water pitchers were filled with milk so that either the prisoners remained thirsty or broke their strike; nobody faltered and the impasse continued. The authorities then attempted force-feeding the prisoners but this was resisted.[45][f] With the matter still unresolved, the Indian Viceroy, Lord Irwin, cut short his vacation in Simla to discuss the situation with jail authorities.[47] Since the activities of the hunger strikers had gained popularity and attention amongst the people nationwide, the government decided to advance the start of the Saunders murder trial, which was henceforth called the Lahore Conspiracy Case. Singh was transported to Borstal Jail, Lahore,[48] and the trial began there on 10 July 1929. In addition to charging them with the murder of Saunders, Singh and the 27 other prisoners were charged with plotting a conspiracy to murder Scott, and waging a war against the King.[38] Singh, still on hunger strike, had to be carried to the court handcuffed on a stretcher; he had lost 14 pounds (6.4 kg) from his original weight of 133 pounds (60 kg) since beginning the strike.[48]The government was beginning to make concessions but refused to move on the core issue of recognising the classification of "political prisoner". In the eyes of officials, if someone broke the law then that was a personal act, not a political one, and they were common criminals.[22] By now, the condition of another hunger striker, Jatindra Nath Das, lodged in the same jail, had deteriorated considerably. The Jail committee recommended his unconditional release, but the government rejected the suggestion and offered to release him on bail. On 13 September 1929, Das died after a 63-day hunger strike.[48] Almost all the nationalist leaders in the country paid tribute to Das' death. Mohammad Alam and Gopi Chand Bhargava resigned from the Punjab Legislative Council in protest, and Nehru moved a successful adjournment motion in the Central Assembly as a censure against the "inhumane treatment" of the Lahore prisoners.[49] Singh finally heeded a resolution of the Congress party, and a request by his father, ending his hunger strike on 5 October 1929 after 116 days.[38] During this period, Singh's popularity among common Indians extended beyond Punjab.[22][50]Singh's attention now turned to his trial, where he was to face a Crown prosecution team comprising C. H. Carden-Noad, Kalandar Ali Khan, Jai Gopal Lal, and the prosecuting inspector, Bakshi Dina Nath.[38] The defence was composed of eight lawyers. Prem Dutt Verma, the youngest amongst the 27 accused, threw his slipper at Gopal when he turned and became a prosecution witness in court. As a result, the magistrate ordered that all the accused should be handcuffed.[38] Singh and others refused to be handcuffed and were subjected to brutal beating.[51] The revolutionaries refused to attend the court and Singh wrote a letter to the magistrate citing various reasons for their refusal.[52][53] The magistrate ordered the trial to proceed without the accused or members of the HSRA. This was a setback for Singh as he could no longer use the trial as a forum to publicise his views.[54]Special Tribunal

To speed up the slow trial, the Viceroy, Lord Irwin, declared an emergency on 1 May 1930 and introduced an ordinance to set up a special tribunal composed of three high court judges for the case. This decision cut short the normal process of justice as the only appeal after the tribunal was to the Privy Council located in England.[38]On 2 July 1930, a habeas corpus petition was filed in the High Court challenging the ordinance on the grounds that it was ultra vires and, therefore, illegal; the Viceroy had no powers to shorten the customary process of determining justice.[38] The petition argued that the Defence of India Act 1915 allowed the Viceroy to introduce an ordinance, and set up such a tribunal, only under conditions of a breakdown of law-and-order, which, it was claimed in this case, had not occurred. However, the petition was dismissed as being premature.[55]Carden-Noad presented the government's charges of conducting robberies, and the illegal acquisition of arms and ammunition among others.[38] The evidence of G. T. H. Hamilton Harding, the Lahore superintendent of police, shocked the court. He stated that he had filed the first information report against the accused under specific orders from the chief secretary to the governor of Punjab and that he was unaware of the details of the case. The prosecution depended mainly on the evidence of P. N. Ghosh, Hans Raj Vohra, and Jai Gopal who had been Singh's associates in the HSRA. On 10 July 1930, the tribunal decided to press charges against only 15 of the 18 accused and allowed their petitions to be taken up for hearing the next day. The trial ended on 30 September 1930.[38] The three accused, whose charges were withdrawn, included Dutt who had already been given a life sentence in the Assembly bomb case.[56]The ordinance (and the tribunal) would lapse on 31 October 1930 as it had not been passed by the Central Assembly or the British Parliament. On 7 October 1930, the tribunal delivered its 300-page judgement based on all the evidence and concluded that the participation of Singh, Sukhdev, and Rajguru in Saunder's murder was proven. They were sentenced to death by hanging.[38] Of the other accused, three were acquitted (Ajoy Ghosh, Jatindra Nath Sanyal and Des Raj), Kundan Lal received seven years' rigorous imprisonment, Prem Dutt received five years of the same, and the remaining seven (Kishori Lal, Mahabir Singh, Bijoy Kumar Sinha, Shiv Verma, Gaya Prashad, Jai Dev and Kamalnath Tewari) were all sentenced to transportation for life.[57]Appeal to the Privy Council

In Punjab province, a defence committee drew up a plan to appeal to the Privy Council. Singh was initially against the appeal but later agreed to it in the hope that the appeal would popularise the HSRA in Britain. The appellants claimed that the ordinance which created the tribunal was invalid while the government countered that the Viceroy was completely empowered to create such a tribunal. The appeal was dismissed by Judge Viscount Dunedin.[58]Reactions to the judgement

After the rejection of the appeal to the Privy Council, Congress party president Madan Mohan Malviya filed a mercy appeal before Irwin on 14 February 1931.[59] Some prisoners sent Mahatma Gandhi an appeal to intervene.[38] In his notes dated 19 March 1931, the Viceroy recorded:The Communist Party of Great Britain expressed its reaction to the case:A plan to rescue Singh and fellow HSRA inmates from the jail failed. HSRA member Durga Devi's husband, Bhagwati Charan Vohra, attempted to manufacture bombs for the purpose, but died when they exploded accidentally.[61]Execution

Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev were sentenced to death in the Lahore conspiracy case and ordered to be hanged on 24 March 1931. The schedule was moved forward by 11 hours and the three were hanged on 23 March 1931 at 7:30 pm[62] in the Lahore jail. It is reported that no magistrate at the time was willing to supervise Singh's hanging as was required by law. The execution was supervised instead by an honorary judge, who also signed the three death warrants, as their original warrants had expired.[63] The jail authorities then broke a hole in the rear wall of the jail, removed the bodies, and secretly cremated the three men under cover of darkness outside Ganda Singh Wala village, and then threw the ashes into the Sutlej river, about 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) from Ferozepore.[64]Criticism of the tribunal trial

Singh's trial has been described by the Supreme Court as "contrary to the fundamental doctrine of criminal jurisprudence" because there was no opportunity for the accused to defend themselves.[65] The Special Tribunal was a departure from the normal procedure adopted for a trial and its decision could only be appealed to the Privy Council located in Britain.[38] The accused were absent from the court and the judgement was passed ex-parte.[54] The ordinance, which was introduced by the Viceroy to form the Special Tribunal, was never approved by the Central Assembly or the British Parliament, and it eventually lapsed without any legal or constitutional sanctity.[66]Reactions to the executions

The executions were reported widely by the press, especially as they took place on the eve of the annual convention of the Congress party at Karachi.[67] Gandhi faced black flag demonstrations by angry youths who shouted "Down with Gandhi".[17] The New York Times reported:Hartals and strikes of mourning were called.[69] The Congress party, during the Karachi session, declared:In the issue of Young India of 29 March 1931, Gandhi wrote:Gandhi controversy

There have been suggestions that Gandhi had an opportunity to stop Singh's execution but refrained from doing so. Another theory is that Gandhi actively conspired with the British to have Singh executed. In contrast, Gandhi's supporters argue that he did not have enough influence with the British to stop the execution, much less arrange it,[72] but claim that he did his best to save Singh's life.[73] They also assert that Singh's role in the independence movement was no threat to Gandhi's role as its leader, so he would have no reason to want him dead.[24] Gandhi always maintained that he was a great admirer of Singh's patriotism. He also stated that he was opposed to Singh's execution (and for that matter, capital punishment in general) and proclaimed that he had no power to stop it.[72] Of Singh's execution Gandhi said: "The government certainly had the right to hang these men. However, there are some rights which do credit to those who possess them only if they are enjoyed in name only."[74] Gandhi also once remarked about capital punishment: "I cannot in all conscience agree to anyone being sent to the gallows. God alone can take life, because he alone gives it."[75] Gandhi had managed to have 90,000 political prisoners, who were not members of his Satyagraha movement, released under the Gandhi-Irwin Pact.[24]According to a report in the Indian magazine Frontline, he did plead several times for the commutation of the death sentences of Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev, including a personal visit on 19 March 1931. In a letter to the Viceroy on the day of their execution, he pleaded fervently for commutation, not knowing that the letter would arrive too late.[24] Lord Irwin, the Viceroy, later said:Ideals and opinions

Singh's ideal was Kartar Singh Sarabha. He regarded Kartar Singh, the founding-member of the Ghadar Party as his hero. Bhagat was also inspired by Bhai Parmanand, another founding-member of the Ghadar Party.[76] Singh was attracted to anarchism and communism.[77] He was an avid reader of the teachings of Mikhail Bakunin and also read Karl Marx, Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky.[78] In his last testament, "To Young Political Workers", he declares his ideal as the "Social reconstruction on new, i.e., Marxist, basis".[79]Singh did not believe in the Gandhian ideology—which advocated Satyagraha and other forms of non-violent resistance, and felt that such politics would replace one set of exploiters with another.[80]From May to September 1928, Singh published a series of articles on anarchism in Kirti. He was concerned that the public misunderstood the concept of anarchism, writing that: "The people are scared of the word anarchism. The word anarchism has been abused so much that even in India revolutionaries have been called anarchist to make them unpopular." In his opinion, anarchism refers to the absence of a ruler and abolition of the state, not the absence of order, and: "I think in India the idea of universal brotherhood, the Sanskrit sentence vasudhaiva kutumbakam etc., has the same meaning." He believed that:Historian K. N. Panikkar described Singh as one of the early Marxists in India.[80] The political theorist Jason Adams notes that he was more enamoured with Lenin than with Marx.[78] From 1926 onward, he studied the history of the revolutionary movements in India and abroad. In his prison notebooks, he quoted Lenin in reference to imperialism and capitalism and also the revolutionary thoughts of Trotsky.[77] When asked what his last wish was, Singh replied that he was studying the life of Lenin and he wanted to finish it before his death.[81] In spite of his belief in Marxist ideals however, Singh never joined the Communist Party of India.[78]Atheism

Wikisource has original text related to this article: Singh began to question religious ideologies after witnessing the Hindu–Muslim riots that broke out after Gandhi disbanded the Non-Cooperation Movement. He did not understand how members of these two groups, initially united in fighting against the British, could be at each other's throats because of their religious differences.[82] At this point, Singh dropped his religious beliefs, since he believed religion hindered the revolutionaries' struggle for independence, and began studying the works of Bakunin, Lenin, Trotsky – all atheist revolutionaries. He also took an interest in Soham Swami's book Common Sense,[g][83]While in prison in 1930–31, Bhagat Singh was approached by Randhir Singh, a fellow inmate, and a Sikh leader who would later found the Akhand Kirtani Jatha. According to Bhagat Singh's close associate Shiva Verma, who later compiled and edited his writings, Randhir Singh tried to convince Bhagat Singh of the existence of God, and upon failing berated him: "You are giddy with fame and have developed an ego that is standing like a black curtain between you and God".[84][h] In response, Bhagat Singh wrote an essay entitled "Why I am an Atheist" to address the question of whether his atheism was born out of vanity. In the essay, he defended his own beliefs and said that he used to be a firm believer in the Almighty, but could not bring himself to believe the myths and beliefs that others held close to their hearts.[86] He acknowledged the fact that religion made death easier, but also said that unproven philosophy is a sign of human weakness.[84] In this context, he noted:Towards the end of the essay, Bhagat Singh wrote:"Killing the ideas"

In the leaflet he threw in the Central Assembly on 9 April 1929, he stated: "It is easy to kill individuals but you cannot kill the ideas. Great empires crumbled, while the ideas survived."[87][better source needed] While in prison, Singh and two others had written a letter to Lord Irwin, wherein they asked to be treated as prisoners of war and consequently to be executed by firing squad and not by hanging.[88] Prannath Mehta, Singh's friend, visited him in the jail on 20 March, four days before his execution, with a draft letter for clemency, but he declined to sign it.[24]Reception

Singh was criticised both by his contemporaries,[who?] and by people after his death,[who?] for his violent and revolutionary stance towards the British as well as his strong opposition to the pacifist stance taken by Gandhi and the Indian National Congress.[89][90] The methods he used to convey his message, such as shooting Saunders, and throwing non-lethal bombs, stood in stark contrast to Gandhi's non-violent methodology.[90]Popularity

Subhas Chandra Bose said that: "Bhagat Singh had become the symbol of the new awakening among the youths." Nehru acknowledged that Bhagat Singh's popularity was leading to a new national awakening, saying: "He was a clean fighter who faced his enemy in the open field ... he was like a spark that became a flame in a short time and spread from one end of the country to the other dispelling the prevailing darkness everywhere".[17] Four years after Singh's hanging, the Director of the Intelligence Bureau, Sir Horace Williamson, wrote: "His photograph was on sale in every city and township and for a time rivaled in popularity even that of Mr. Gandhi himself".[17]Legacy and memorials

Bhagat Singh remains a significant figure in Indian iconography to the present day.[91] His memory, however, defies categorisation and presents problems for various groups that might try to appropriate it. Pritam Singh, a professor who has specialised in the study of federalism, nationalism and development in India, notes that- On 15 August 2008, an 18-foot tall bronze statue of Singh was installed in the Parliament of India, next to the statues of Indira Gandhi and Subhas Chandra Bose.[93] A portrait of Singh and Dutt also adorns the walls of the Parliament House.[94]

- The place where Singh was cremated, at Hussainiwala on the banks of the Sutlej river, became Pakistani territory during the partition. On 17 January 1961, it was transferred to India in exchange for 12 villages near the Sulemanki Headworks.[64] Batukeshwar Dutt was cremated there on 19 July 1965 in accordance with his last wishes, as was Singh's mother, Vidyawati.[95] The National Martyrs Memorial was built on the cremation spot in 1968[96] and has memorials of Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev. During the 1971 India–Pakistan war, the memorial was damaged and the statues of the martyrs were removed by the Pakistani Army. They have not been returned[64][97] but the memorial was rebuilt in 1973.[95]

- The Shaheedi Mela (Punjabi: Martyrdom Fair) is an event held annually on 23 March when people pay homage at the National Martyrs Memorial.[98] The day is also observed across the Indian state of Punjab.[99]

- The Shaheed-e-Azam Sardar Bhagat Singh Museum opened on the 50th anniversary of his death at his ancestral village, Khatkar Kalan. Exhibits include Singh's ashes, the blood-soaked sand, and the blood-stained newspaper in which the ashes were wrapped.[100] A page of the first Lahore Conspiracy Case's judgement in which Kartar Singh Sarabha was sentenced to death and on which Singh put some notes is also displayed,[100] as well as a copy of the Bhagavad Gita with Bhagat Singh's signature, which was given to him in the Lahore Jail, and other personal belongings.[101][102]

- The Bhagat Singh Memorial was built in 2009 in Khatkar Kalan at a cost of ₹168 million (US$2.3 million).[103]

- The Supreme Court of India established a museum to display landmarks in the history of India's judicial system, displaying records of some historic trials. The first exhibition that was organised was the Trial of Bhagat Singh, which opened on 28 September 2007, on the centenary celebrations of Singh's birth.[65][66]

Modern days

The youth of India still draw tremendous amount of inspiration from Singh.[104][105][106] He was voted the "Greatest Indian" in a poll by the Indian magazine India Today in 2008, ahead of Bose and Gandhi.[107] During the centenary of his birth, a group of intellectuals set up an institution named Bhagat Singh Sansthan to commemorate him and his ideals.[108] The Parliament of India paid tributes and observed silence as a mark of respect in memory of Singh on 23 March 2001[109] and 2005.[110] In Pakistan, after a long-standing demand by activists from the Bhagat Singh Memorial Foundation of Pakistan, the Shadman Chowk square in Lahore, where he was hanged, was renamed as Bhagat Singh Chowk. This change was successfully challenged in a Pakistani court.[111][112] On 6 September 2015, the Bhagat Singh Memorial Foundation filed a petition in the Lahore high court and again demanded the renaming of the Chowk to Bhagat Singh Chowk.[113]Films and television

Several films have been made portraying the life and times of Singh. The first film based on his life was Shaheed-e-Azad Bhagat Singh (1954) in which Prem Abeed played the role of Singh followed by Shaheed Bhagat Singh (1963), starring Shammi Kapoor as Bhagat Singh, Shaheed (1965) in which Manoj Kumar portrayed Bhagat Singh and Amar Shaheed Bhagat Singh (1974) in which Som Dutt portrays Singh. Three films about Singh were released in 2002 Shaheed-E-Azam, 23 March 1931: Shaheed and The Legend of Bhagat Singh in which Singh was portrayed by Sonu Sood, Bobby Deol and Ajay Devgn respectively.[114][115]Siddharth played the role of Bhagat singh in the 2006 film Rang De Basanti, a film drawing parallels between revolutionaries of Bhagat Singh's era and modern Indian youth.[116] Gurdas Mann played the role of Singh in Shaheed Udham Singh, a film based on life of Udham Singh. Karam Rajpal portrayed Bhagat Singh in Star Bharat's television series Chandrashekhar, which is based on life of Chandra Shekhar Azad.[117]In 2008, Nehru Memorial Museum and Library (NMML) and Act Now for Harmony and Democracy (ANHAD), a non-profit organisation, co-produced a 40-minute documentary on Bhagat Singh entitled Inqilab, directed by Gauhar Raza.[118][119]Theatre

Singh, Sukhdev and Rajguru have been the inspiration for a number of plays in India and Pakistan, that continue to attract crowds.[120][121][122]Songs

Although created by Ram Prasad Bismil, the patriotic Hindustani songs, "Sarfaroshi ki Tamanna" ("The desire to sacrifice") and "Mera Rang De Basanti Chola" ("O Mother! Dye my robe the colour of spring"[123]) are largely associated with Singh and have been used in a number of related films.[124]Other

In 1968, a postage stamp was issued in India commemorating the 61st birth anniversary of Singh.[125] A ₹5 coin commemorating him was released for circulation in 2012.[126]References

Notes

- ^ a b c The date of Singh's birth is subject to dispute. Commonly thought to be born on either 27[1] or 28[2] September 1907, some biographers believe that the evidence points to 19 October 1907.[3]

- ^ Although some sources claim that Swaran Singh died after leaving jail, a letter written by Bhagat Singh as a student described his death as occurring while he was imprisoned.[9]

- ^ The National College inside Bradlaugh Hall, Lahore, had been founded by Lala Lajpat Raito provide an alternative source of education for people who did not want to use schools operated by the British.[14]

- ^ He was secretary of the Kirti Kisan Party when it organised an all-India meeting of revolutionaries in September 1928 and he later became its leader.[11]

- ^ Opposition in India to the Simon Commission was not universal. For example, the Central Sikh League, some Hindu politicians, and some members of the Muslim League agreed to co-operate[22]

- ^ An example of the methods adopted to counterattack attempts at force-feeding is the swallowing of red pepper and boiling water by a prisoner called Kishori Lal. This combination made his throat too sore to permit entry of the feeding tube.[46]

- ^ Singh incorrectly referred to Niralamba Swami as the author of the book, however Niralamba had only written the introduction.

- ^ In his own account of the meeting though, Randhir Singh says that Bhagat Singh repented for giving up his religion and said that he did so only under the influence of irreligious people and in search of personal glory. Certain Sikh groups periodically attempt to reclaim Bhagat Singh as a Sikh based on Randhir Singh's writings.[85]

Dadabhai Naoroji

Dadabhai Naoroji

दादाभाई नौरोजी Dadabhai Naoroji c. 1889

Dadabhai Naoroji c. 1889Member of Parliament

for Finsbury CentralIn office

1892–1895Preceded by Frederick Thomas Penton Succeeded by William Frederick Barton Massey-Mainwaring Majority 3 Personal details Born 4 September 1825

Bombay, British IndiaDied 30 June 1917 (aged 93)

Bombay, British IndiaPolitical party Liberal Other political

affiliationsIndian National Congress Spouse(s) Gulbaai Residence London, United Kingdom Alma mater University of Mumbai Profession Academician, politician Committees Legislative Council of Mumbai Signature  Dadabhai Naoroji (4 September 1825 – 30 June 1917), known as the Grand Old Man of India, was a Parsi intellectual, educator, cotton trader, and an early Indian political and social leader. He was a Liberal Party member of Parliament (MP) in the United Kingdom House of Commons between 1892 and 1895, and the first Indian to be a British MP,[1][2] notwithstanding the Anglo-Indian MP David Ochterlony Dyce Sombre, who was disenfranchised for corruption.Naoroji is also credited with the founding of the Indian National Congress, along with A.O. Hume and Dinshaw Edulji Wacha. His book Poverty and Un-British Rule in India[2] brought attention to the draining of India's wealth into Britain. He was also a member of the Second International along with Kautsky and Plekhanov .In 2014, Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg inaugurated the Dadabhai Naoroji Awards for services to UK-India relations.[3]India Post dedicated a stamp to Naoroji on 29 December 2017, on the occasion of his 100th death anniversary.[4][5]

Dadabhai Naoroji (4 September 1825 – 30 June 1917), known as the Grand Old Man of India, was a Parsi intellectual, educator, cotton trader, and an early Indian political and social leader. He was a Liberal Party member of Parliament (MP) in the United Kingdom House of Commons between 1892 and 1895, and the first Indian to be a British MP,[1][2] notwithstanding the Anglo-Indian MP David Ochterlony Dyce Sombre, who was disenfranchised for corruption.Naoroji is also credited with the founding of the Indian National Congress, along with A.O. Hume and Dinshaw Edulji Wacha. His book Poverty and Un-British Rule in India[2] brought attention to the draining of India's wealth into Britain. He was also a member of the Second International along with Kautsky and Plekhanov .In 2014, Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg inaugurated the Dadabhai Naoroji Awards for services to UK-India relations.[3]India Post dedicated a stamp to Naoroji on 29 December 2017, on the occasion of his 100th death anniversary.[4][5]Contents

Early life[edit]

Naoroji was born in Bombay into a Gujarati-speaking Parsi family, and educated at the Elphinstone Institute School.[6] He was patronised by the Maharaja of Baroda, Sayajirao Gaekwad III, and started his public life as the Dewan (Minister) to the Maharaja in 1874. Being an Athornan (ordained priest), Naoroji founded the Rahnumae Mazdayasne Sabha (Guides on the Mazdayasne Path) on 1 August 1851 to restore the Zoroastrian religion to its original purity and simplicity. In 1854, he also founded a Gujarati fortnightly publication, the Rast Goftar (or The Truth Teller), to clarify Zoroastrian concepts and promote Parsi social reforms.[7] In 1855, he was appointed Professor of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy at the Elphinstone College in Bombay,[8] becoming the first Indian to hold such an academic position. He travelled to London in 1855 to become a partner in Cama & Co, opening a Liverpool location for the first Indian company to be established in Britain. Within three years, he had resigned on ethical grounds. In 1859, he established his own cotton trading company, Dadabhai Naoroji & Co. Later, he became professor of Gujarati at University College London.In 1865, Naoroji directed the launch the London Indian Society, the purpose of which was to discuss Indian political, social and literary subjects.[9] In 1861 Naoroji founded The Zoroastrian Trust Funds of Europe alongside Muncherjee Hormusji Cama[10] In 1867 Naoroji also helped to establish the East India Association, one of the predecessor organisations of the Indian National Congress with the aim of putting across the Indian point of view before the British public. The Association was instrumental in counter-acting the propaganda by the Ethnological Society of London which, in its session in 1866, had tried to prove the inferiority of the Asians to the Europeans. This Association soon won the support of eminent Englishmen and was able to exercise considerable influence in the British Parliament. In 1874, he became Prime Minister of Baroda and was a member of the Legislative Council of Mumbai (1885–88). He was also a member of the Indian National Association founded by Sir Surendranath Banerjee from Calcutta a few years before the founding of the Indian National Congress in Bombay, with the same objectives and practices. The two groups later merged into the INC, and Naoroji was elected President of the Congress in 1886. Naoroji published Poverty and un-British Rule in India in 1901.Elected to the British House of Commons as a result of the 1892 election, he served until 1895.[11] During his time he put his efforts towards improving the situation in India. He had a very clear vision and was an effective communicator. He set forth his views about the situation in India over the course of history of the governance of the country and the way in which the colonial rulers rules.Naoroji moved to Britain once again and continued his political involvement. Elected for the Liberal Party in Finsbury Central at the 1892 general election, he was the first British Indian MP.[12] He refused to take the oath on the Bible as he was not a Christian, but was allowed to take the oath of office in the name of God on his copy of Khordeh Avesta. In Parliament, he spoke on Irish Home Rule and the condition of the Indian people. He was also a notable Freemason. In his political campaign and duties as an MP, he was assisted by Muhammed Ali Jinnah, the future Muslim nationalist and founder of Pakistan. In 1906, Naoroji was again elected president of the Indian National Congress. Naoroji was a staunch moderate within the Congress, during the phase when opinion in the party was split between the moderates and extremists. Naoroji was a mentor to Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Gopal Krishna Gokhale and Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. He was married to Gulbai at the age of eleven. He died in Bombay on 30 June 1917, at the age of 91. Today the Dadabhai Naoroji Road, a heritage road of Mumbai, is named after him. Also, the Dadabhai Naoroji Road in Karachi, Pakistan is also named after him as well, as Naoroji Street in the Finsbury area of London. A prominent residential colony for central government servants in the south of Delhi is also named Naoroji Nagar. His granddaughters Perin and Khrushedben were also involved in the freedom struggle. In 1930, Khurshedben was arrested along with other revolutionaries for attempting to hoist the Indian flag in a Government College in Ahmedabad.[13]Naoroji's drain theory and poverty[edit]

Dadabhai Naoroji's work focused on the drain of wealth from India into England during colonial rule of British in India.[14] One of the reasons that the Drain theory is attributed to Naoroji is his decision to estimate the net national profit of India, and by extension, the effect that colonisation has on the country. Through his work with economics, Naoroji sought to prove that Britannia was draining money out of India.[15] Naoroji described 6 factors which resulted in the external drain. Firstly, India is governed by a foreign government. Secondly, India does not attract immigrants which bring labour and capital for economic growth. Thirdly, India pays for Britain's civil administrations and occupational army. Fourthly, India bears the burden of empire building in and out of its borders. Fifthly, opening the country to free trade was actually a way to exploit India by offering highly paid jobs to foreign personnel. Lastly, the principal income-earners would buy outside of India or leave with the money as they were mostly foreign personnel.[16] In Naoroji's book 'Poverty' he estimated a 200–300 million pounds loss of India's revenue to Britain that is not returned. Naoroji described this as vampirism, with money being a metaphor for blood, which humanised India and attempted to show Britain's actions as monstrous in an attempt to garner sympathy for the nationalist movement.[17]When referring to the Drain, Naoroji stated that he believed some tribute was necessary as payment for the services that England brought to India such as the railways. However the money from these services were being drained out of India; for instance the money being earned by the railways did not belong to India, which supported his assessment that India was giving too much to Britain. India was paying tribute for something that was not bringing profit to the country directly. Instead of paying off foreign investment which other countries did, India was paying for services rendered despite the operation of the railway being already profitable for Britain. This type of drain was experienced in different ways as well, for instance, British workers earning wages that were not equal with the work that they have done in India, or trade that undervalued India's goods and overvalued outside goods.[18] Englishmen were encouraged to take on high paying jobs in India, and the British government allowed them to take a portion of their income back to Britain. Furthermore, the East India Company was purchasing Indian goods with money drained from India to export to Britain, which was a way that the opening up of free trade allowed India to be exploited.[19]When elected to Parliament by a narrow margin of 5 votes his first speech was about questioning Britain's role in India. Naoroji explained that Indians were either British subjects or British slaves, depending on how willing Britain was to give India the institutions that Britain already operated. By giving these institutions to India it would allow India to govern itself and as a result the revenue would stay in India.[20] It is because Naoroji identified himself as an Imperial citizen that he was able to address the economic hardships facing India to an English audience. By presenting himself as an Imperial citizen he was able to use rhetoric to show the benefit to Britain that an ease of financial burden on India would have. He argued that by allowing the money earned in India to stay in India, tributes would be willingly and easily paid without fear of poverty; he argued that this could be done by giving equal employment opportunities to Indian professionals who consistently took jobs they were over-qualified for. Indian labour would be more likely to spend their income within India preventing one aspect of the drain.[21] Naoroji believed that to solve the problem of the drain it was important to allow India to develop industries; this would not be possible without the revenue draining from India into England.It was also important to examine British and Indian trade to prevent the end of budding industries due to unfair valuing of goods and services.[22] By allowing industry to grow in India, tribute could be paid to Britain in the form of taxation and the increase in interest for British goods in India. Over time, Naoroji became more extreme in his comments as he began to lose patience with Britain. This was shown in his comments which became increasingly aggressive. Naoroji showed how the ideologies of Britain conflicted when asking them if they would allow French youth to occupy all the lucrative posts in England. He also brought up the way that Britain objected to the drain of wealth to the papacy during the 16th century.[23] Naoroji's work on the drain theory was the main reason behind the creation of the Royal Commission on Indian Expenditure in 1896 in which he was also a member. This commission reviewed financial burdens on India and in some cases came to the conclusion that those burdens were misplaced.[24]Views and legacy[edit]

Dadabhai Naoroji is regarded as one of the most important Indians during the independence movement. In his writings, he considered that the foreign intervention into India was clearly not favourable for the country.Naoroji is remembered as the "Grand Old Man of Indian Nationalism"Mahatma Gandhi wrote to Naoroji in a letter of 1894 that "The Indians look up to you as children to the father. Such is really the feeling here."[26]Bal Gangadhar Tilak admired him; he said:Here are the significant extracts taken from his speech delivered before the East India Association on 2 May 1867 regarding what educated Indians expect from their British rulers."In this Memorandum I desire to submit for the kind and generous consideration of His Lordship the Secretary of State for India, that from the same cause of the deplorable drain [of economic wealth from India to England], besides the material exhaustion of India, the moral loss to her is no less sad and lamentable . . . All [the Europeans] effectually do is to eat the substance of India, material and moral, while living there, and when they go, they carry away all they have acquired . . . The thousands [of Indians] that are being sent out by the universities every year find themselves in a most anomalous position. There is no place for them in their motherland . . . What must be the inevitable consequence? . . . despotism and destruction . . . or destroying hand and power. "In this above quotation he explains his theory in which the British used India as a drain of wealth.A plaque referring to Dadabhai Naoroji is located outside the Finsbury Town Hall on Rosebery Avenue, London.Works[edit]

- The manners and customs of the Parsees (Bombay, 1864)

- The European and Asiatic races (London, 1866)

- Admission of educated natives into the Indian Civil Service (London, 1868)

- The wants and means of India (London, 1876)

- Condition of India (Madras, 1882)

- Poverty of India

- A Paper Read Before the Bombay Branch of the East India Association, Bombay, Ranima Union Press, (1876)

- C. L. Parekh, ed., Essays, Speeches, Addresses and Writings of the Honourable Dadabhai Naoroji, Bombay, Caxton Printing Works (1887). An excerpt, "The Benefits of British Rule", in a modernised text by J. S. Arkenberg, ed., on line at Paul Halsall, ed., Internet Modern History Sourcebook.

- Lord Salisbury's Blackman (Lucknow, 1889)

- Naoroji, Dadabhai (1861). The Parsee Religion. University of London.

- Dadabhai Naoroji (1902). Poverty and Un-British Rule in India. Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India.; Commonwealth Publishers, 1988. ISBN 81-900066-2-2

He made the first attempt to estimate national income of India in 1867.See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Sumita Mukherjee. "'Narrow-majority' and 'Bow-and-agree': Public Attitudes Towards the Elections of the First Asian MPs in Britain, Dadabhai Naoroji and Mancherjee Merwanjee Bhownaggree, 1885–1906" (PDF). Journal of the Oxford University History Society (2 (Michaelmas 2004)).

- ^ a b

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Naoroji, Dadabhai". Encyclopædia Britannica. 17(11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 167.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Naoroji, Dadabhai". Encyclopædia Britannica. 17(11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 167. - ^ "Dadabhai Naoroji Awards presented for the first time - GOV.UK". www.gov.uk. Retrieved 2017-06-01.

- ^ "India Post Honors Dadabhai Naoroji With Stamp - Parsi Times". Parsi Times. 2018-01-06. Retrieved 2018-05-19.

- ^ "India Post Issued Stamp on Dadabhai Naoroji". Phila-Mirror. 2017-12-29. Retrieved 2018-05-19.

- ^ Dilip Hiro (2015). The Longest August: The Unflinching Rivalry Between India and Pakistan. Nation Books. p. 9. ISBN 9781568585031. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ^ Mohanram, edited by Ralph J. Crane & Radhika (2000). Shifting continents/colliding cultures : diaspora writing of the Indian subcontinent. Amsterdam: Rodopi. p. 62. ISBN 9042012617. Retrieved 13 December 2015.

- ^ Sanjay Mistry "Naorojiin, Dadabhai" in David Dabydeen (et al, eds) The Oxford Companion of Black British History, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007, p.336-7

- ^ Fourteenth Annual General Meeting of the British Indian Association, 14 February 1866, p.22 British Indian Association

- ^ John R. Hinnells (28 April 2005). The Zoroastrian Diaspora: Religion and Migration. OUP Oxford. p. 388. ISBN 978-0-19-826759-1. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- ^ "From the archive, 26 July 1892: Britain's first Asian MP elected", The Guardian, 26 July 2013, retrieved 2 May 2018

- ^ Peters, K. J. (29 May 1946). "Indian Patchwork Is Made of Many Colours". Aberdeen Journal. Retrieved 2 December 2014 – via British Newspaper Archive. (Subscription required (help)).

- ^ "Millionaire's daughter arrested". Portsmouth Evening News. 21 August 1930. Retrieved 2 December 2014 – via British Newspaper Archive. (Subscription required (help)).

- ^ Ganguli B.N. "Dadabhai Naoroji and The Drain Theory" The Journal of Asian Studies 26.4 (August 1967) 728–729.23, February 2013.

- ^ "Raychaudhuri G.S. "On Some Estimates of National Income Indian Economy 1858–1947" Economic and Political Weekly 1.16 (December 1966) 673–679. JSTOR. Web. 23, February 2013.

- ^ Ganguli B.N. "Dadabhai Naoroji and the Mechanism of External Drain" Indian Economic and Social History Review 2.2 (1964) 85–102, Scholars Portal. Web. 24, February 2013

- ^ Banerjee, Sukanya "Becoming Imperial Citizens : Indians in the Late Victorian Empire Durham" Duke University Press, 2010. Ebrary. Web. 24 February. 2013.'

- ^ ^Ganguli B.N.

- ^ Doctor Adi. H. "Political Thinkers of Modern India" New Delhi Mittal Publications, 1997. Google Book Search. Web. 26 February 2013.

- ^ Chatterjee, Partha "Modernity, Democracy and a Political Negotiation of Death" South Asia Research 19.2. (1999) 103–119, Scholars Portal. Web. 24 February 2013

- ^ ^Banerjee, Sukanya

- ^ ^Doctor Adi. H.

- ^ Chandra, Bipan "Indian Nationalists and the Drain, 1880–1905" Indian Economic And Social History Review 2.2 (January 1964) 103–114, Scholars Portal. Web. 26 February 2013

- ^ Edited by Chishti, M. Anees "Committees And Commissions in Pre-Independence India 1836–1947 Volume 2: 1882–1895" New Delhi Mittal Publications, 2001. Search Google Books. Web. 26 February 2013.

- ^ "Transactions of the Ethnological Society of London", p. 9

- ^ "Gandhi and Indians in South Africa", p. 37, by Shiri Ram Bakshi, year = 1988

- ^ "Encyclopedia Eminent Thinkers (vol. 11 : The Political Thought of Dadabhai Naoroji)", p.30 by Ashu Pasrichat

Further reading[edit]

- Rustom P. Masani, Dadabhai Naoroji (1939).

- Munni Rawal, Dadabhai Naoroji, Prophet of Indian Nationalism, 1855–1900, New Delhi, Anmol Publications (1989).

- S. R. Bakshi, Dadabhai Naoroji: The Grand Old Man, Anmol Publications (1991). ISBN 81-7041-426-1

- Verinder Grover, ‘'Dadabhai Naoroji: A Biography of His Vision and Ideas’’ New Delhi, Deep & Deep Publishers (1998) ISBN 81-7629-011-4

- Debendra Kumar Das, ed., ‘'Great Indian Economists : Their Creative Vision for Socio-Economic Development.’’ Vol. I: ‘Dadabhai Naoroji (1825–1917) : Life Sketch and Contribution to Indian Economy.’’ New Delhi, Deep and Deep (2004). ISBN 81-7629-315-6

- P. D. Hajela, ‘'Economic Thoughts of Dadabhai Naoroji,’’ New Delhi, Deep & Deep (2001). ISBN 81-7629-337-7

- Pash Nandhra, entry Dadabhai Naoroji in Brack et al. (eds).Dictionary of Liberal History; Politico's, 1998

- Zerbanoo Gifford, Dadabhai Naoroji: Britain's First Asian MP; Mantra Books, 1992

- Codell, J. "Decentering & Doubling Imperial Discourse in the British Press: D. Naoroji & M. M. Bhownaggree," Media History 15 (Fall 2009), 371–84.

- Metcalf and Metcalf, Concise History of India