1.Vallabhbhai Patel

|

Vallabhbhai Patel

| |

|---|---|

| |

| 1st Deputy Prime Minister of India | |

| In office 15 August 1947 – 15 December 1950 | |

| Monarch | George VI |

| President | Rajendra Prasad |

| Governor General | Louis Mountbatten C. Rajagopalachari |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Minister of Home Affairs | |

| In office 15 August 1947 – 15 December 1950 | |

| Prime Minister | Jawaharlal Nehru |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | C. Rajagopalachari |

| 1st Commander-in-chief of the Indian Armed Forces | |

| In office 15 August 1947 – 15 December 1950 | |

| Monarch | George VI |

| President | Rajendra Prasad |

| Governor General | Louis Mountbatten C. Rajagopalachari |

| Prime Minister | Jawaharlal Nehru |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished (merged to the President of India) |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Vallabhbhai Jhaverbhai Patel

31 October 1875 Nadiad, Bombay Presidency, British India |

| Died | 15 December 1950 (aged 75) Bombay, Bombay State, India |

| Cause of death | Heart attack |

| Political party | Indian National Congress |

| Spouse(s) | Jhaverben Patel |

| Children | Maniben Patel Dahyabhai Patel |

| Mother | Laad Bai |

| Father | Jhaverbhai Patel |

| Alma mater | Middle Temple |

| Profession | |

| Awards | Bharat Ratna (1991) (posthumously) |

Vallabhbhai Jhaverbhai Patel[1][2] (31 October 1875 – 15 December 1950), popularly known as Sardar Patel, was an Indian politician. He served as the first Deputy Prime Minister of India. He was an Indian barrister and statesman, a senior leader of the Indian National Congress and a founding father of the Republic of India who played a leading role in the country's struggle for independence and guided its integration into a united, independent nation.[3] In India and elsewhere, he was often called Sardar, meaning "chief" in Hindi, Urdu, and Persian. He acted as Home Minister during the political integration of India and the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947.[4]

Patel was raised in the countryside of state of Gujarat.[5] He was a successful lawyer. He subsequently organised peasants from Kheda, Borsad, and Bardoli in Gujarat in non-violent civil disobedience against the British Raj, becoming one of the most influential leaders in Gujarat. He was appointed as the 49th President of Indian National Congress, organising the party for elections in 1934 and 1937 while promoting the Quit India Movement.

As the first Home Minister and Deputy Prime Minister of India, Patel organised relief efforts for refugees fleeing to Punjab and Delhi from Pakistan and worked to restore peace. He led the task of forging a united India, successfully integrating into the newly independent nation those British colonial provinces that had been "allocated" to India.[6] Besides those provinces that had been under direct British rule, approximately 565 self-governing princely states had been released from British suzerainty by the Indian Independence Act of 1947. Threatening military force, Patel persuaded almost every princely state to accede to India. His commitment to national integration in the newly independent country was total and uncompromising, earning him the sobriquet "Iron Man of India".[7] He is also remembered as the "patron saint of India's civil servants" for having established the modern all-India services system. He is also called the "Unifier of India".[8] The Statue of Unity, the world's tallest statue, was dedicated to him on 31 October 2018 which is approximately 182 metres (597 ft) in height.

Early life[edit]

Patel's date of birth was never officially recorded; Patel entered it as 31 October on his matriculation examination papers.[10] He belonged to the Leuva Patel Patidar community of Central Gujarat, although after his fame, the Leuva Patels and Kadava Patels have also claimed him as one of their own.[11]

Patel travelled to attend schools in Nadiad, Petlad, and Borsad, living self-sufficiently with other boys. He reputedly cultivated a stoic character. A popular anecdote recounts that he lanced his own painful boil without hesitation, even as the barber charged with doing it trembled.[12] When Patel passed his matriculation at the relatively late age of 22, he was generally regarded by his elders as an unambitious man destined for a commonplace job. Patel himself, though, harboured a plan to study to become a lawyer, work and save funds, travel to England, and become a barrister.[13] Patel spent years away from his family, studying on his own with books borrowed from other lawyers, passing his examinations within two years. Fetching his wife Jhaverba from her parents' home, Patel set up his household in Godhra and was called to the bar. During the many years it took him to save money, Patel – now an advocate – earned a reputation as a fierce and skilled lawyer. The couple had a daughter, Maniben, in 1904 and a son, Dahyabhai, in 1906. Patel also cared for a friend suffering from the Bubonic plague when it swept across Gujarat. When Patel himself came down with the disease, he immediately sent his family to safety, left his home, and moved into an isolated house in Nadiad (by other accounts, Patel spent this time in a dilapidated temple); there, he recovered slowly.[14]

Patel practised law in Godhra, Borsad, and Anand while taking on the financial burdens of his homestead in Karamsad. Patel was the first chairman and founder of "Edward Memorial High School" Borsad, today known as Jhaverbhai Dajibhai Patel High School. When he had saved enough for his trip to England and applied for a pass and a ticket, they were addressed to "V. J. Patel," at the home of his elder brother Vithalbhai, who had the same initials as Vallabhai. Having once nurtured a similar hope to study in England, Vithalbhai remonstrated his younger brother, saying that it would be disreputable for an older brother to follow his younger brother. In keeping with concerns for his family's honour, Patel allowed Vithalbhai to go in his place.[15]

In 1909 Patel's wife Jhaverba was hospitalised in Bombay (now Mumbai) to undergo major surgery for cancer. Her health suddenly worsened and, despite successful emergency surgery, she died in the hospital. Patel was given a note informing him of his wife's demise as he was cross-examining a witness in court. According to witnesses, Patel read the note, pocketed it, and continued his cross-examination and won the case. He broke the news to others only after the proceedings had ended.[16] Patel decided against marrying again. He raised his children with the help of his family and sent them to English-language schools in Mumbai. At the age of 36 he journeyed to England and enrolled at the Middle Temple Inn in London. Completing a 36-month course in 30 months, Patel finished at the top of his class despite having had no previous college background.[17]

Returning to India, Patel settled in Ahmedabad and became one of the city's most successful barristers. Wearing European-style clothes and sporting urbane mannerisms, he became a skilled bridge player. Patel nurtured ambitions to expand his practice and accumulate great wealth and to provide his children with a modern education. He had made a pact with his brother Vithalbhai to support his entry into politics in the Bombay Presidency, while Patel remained in Ahmedabad to provide for the family.[18][19]

Fight for self-rule[edit]

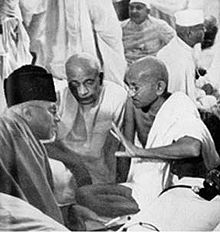

At the urging of his friends, Patel ran in the election for the post of sanitation commissioner of Ahmedabad in 1917 and won. While often clashing with British officials on civic issues, he did not show any interest in politics. Upon hearing of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, he joked to the lawyer and political activist, Ganesh Vasudev Mavlankar, that "Gandhi would ask you if you know how to sift pebbles from wheat. And that is supposed to bring independence." A subsequent meeting with Gandhi, in October 1917 fundamentally changed Patel and led him to join the Indian independence struggle.[20]

In September 1917, Patel delivered a speech in Borsad, encouraging Indians nationwide to sign Gandhi's petition demanding Swaraj – self-rule – from Britain. A month later, he met Gandhi for the first time at the Gujarat Political Conference in Godhra. On Gandhi's encouragement, Patel became the secretary of the Gujarat Sabha, a public body that would become the Gujarati arm of the Indian National Congress. Patel now energetically fought against veth – the forced servitude of Indians to Europeans – and organised relief efforts in the wake of plague and famine in Kheda.[21] The Kheda peasants' plea for exemption from taxation had been turned down by British authorities. Gandhi endorsed waging a struggle there, but could not lead it himself due to his activities in Champaran. When Gandhi asked for a Gujarati activist to devote himself completely to the assignment, Patel volunteered, much to Gandhi's delight.[22] Though his decision was made on the spot, Patel later said that his desire and commitment came after intense personal contemplation, as he realised he would have to abandon his career and material ambitions.[23]

Satyagraha in Gujarat[edit]

Supported by Congress volunteers Narhari Parikh, Mohanlal Pandya, and Abbas Tyabji, Vallabhbhai Patel began a village-by-village tour in the Kheda district, documenting grievances and asking villagers for their support for a statewide revolt by refusing to pay taxes. Patel emphasised the potential hardships and the need for complete unity and non-violence in the face of provocation. He received an enthusiastic response from virtually every village.[24] When the revolt was launched and tax revenue withheld, the government sent police and intimidation squads to seize property, including confiscating barn animals and whole farms. Patel organised a network of volunteers to work with individual villages, helping them hide valuables and protect themselves against raids. Thousands of activists and farmers were arrested, but Patel was not. The revolt evoked sympathy and admiration across India, including among pro-British Indian politicians. The government agreed to negotiate with Patel and decided to suspend the payment of taxes for a year, even scaling back the rate. Patel emerged as a hero to Gujaratis.[25] In 1920 he was elected president of the newly formed Gujarat Pradesh Congress Committee; he would serve as its president until 1945.[citation needed]

Patel supported Gandhi's non-cooperation Movement and toured the state to recruit more than 300,000 members and raise over Rs. 1.5 million in funds.[26] Helping organise bonfires in Ahmedabad in which British goods were burned, Patel threw in all his English-style clothes. Along with his daughter Mani and son Dahya, he switched completely to wearing khadi, the locally produced cotton clothing. Patel also supported Gandhi's controversial suspension of resistance in the wake of the Chauri Chaura incident. In Gujarat he worked extensively in the following years against alcoholism, untouchability, and caste discrimination, as well as for the empowerment of women. In the Congress, he was a resolute supporter of Gandhi against his Swarajist critics. Patel was elected Ahmedabad's municipal president in 1922, 1924, and 1927. During his terms, he oversaw improvements in infrastructure: the supply of electricity was increased, drainage and sanitation systems were extended throughout the city. The school system underwent major reforms. He fought for the recognition and payment of teachers employed in schools established by nationalists (independent of British control) and even took on sensitive Hindu–Muslim issues.[27] Patel personally led relief efforts in the aftermath of the torrential rainfall of 1927 that caused major floods in the city and in the Kheda district, and great destruction of life and property. He established refugee centres across the district, mobilized volunteers, and arranged for supplies of food, medicines, and clothing, as well as emergency funds from the government and the public.[28]

When Gandhi was in prison, Patel was asked by Members of Congress to lead the satyagraha in Nagpur in 1923 against a law banning the raising of the Indian flag. He organised thousands of volunteers from all over the country to take part in processions of people violating the law. Patel negotiated a settlement obtaining the release of all prisoners and allowing nationalists to hoist the flag in public. Later that year, Patel and his allies uncovered evidence suggesting that the police were in league with a local dacoit/ criminal gang related to Devar Baba in the Borsad taluka even as the government prepared to levy a major tax for fighting dacoits in the area. More than 6,000 villagers assembled to hear Patel speak in support of proposed agitation against the tax, which was deemed immoral and unnecessary. He organised hundreds of Congressmen, sent instructions, and received information from across the district. Every village in the taluka resisted payment of the tax and prevented the seizure of property and land. After a protracted struggle, the government withdrew the tax. Historians believe that one of Patel's key achievements was the building of cohesion and trust amongst the different castes and communities, which had been divided along socio-economic lines.[29]

In April 1928 Patel returned to the independence struggle from his municipal duties in Ahmedabad when Bardoli suffered from a serious double predicament of a famine and a steep tax hike. The revenue hike was steeper than it had been in Kheda even though the famine covered a large portion of Gujarat. After cross-examining and talking to village representatives, emphasising the potential hardship and need for non-violence and cohesion, Patel initiated the struggle with a complete denial of taxes.[30] Patel organised volunteers, camps, and an information network across affected areas. The revenue refusal was stronger than in Kheda, and many sympathy satyagrahas were undertaken across Gujarat. Despite arrests and seizures of property and land, the struggle intensified. The situation came to a head in August, when, through sympathetic intermediaries, he negotiated a settlement that included repealing the tax hike, reinstating village officials who had resigned in protest, and returning seized property and land. It was by the women of Bardoli, during the struggle and after the Indian National Congress victory in that area, that Patel first began to be referred to as Sardar (or headman).[31]

As Gandhi embarked on the Dandi Salt March, Patel was arrested in the village of Ras and was put on trial without witnesses, with no lawyer or journalists allowed to attend. Patel's arrest and Gandhi's subsequent arrest caused the Salt Satyagraha to greatly intensify in Gujarat – districts across Gujarat launched an anti-tax rebellion until and unless Patel and Gandhi were released.[32] Once released, Patel served as interim Congress president, but was re-arrested while leading a procession in Mumbai. After the signing of the Gandhi–Irwin Pact, Patel was elected president of Congress for its 1931 session in Karachi – here the Congress ratified the pact and committed itself to the defence of fundamental rights and civil liberties. It advocated the establishment of a secular nation with a minimum wage and the abolition of untouchability and serfdom. Patel used his position as Congress president to organise the return of confiscated land to farmers in Gujarat.[33] Upon the failure of the Round Table Conference in London, Gandhi and Patel were arrested in January 1932 when the struggle re-opened, and imprisoned in the Yeravda Central Jail. During this term of imprisonment, Patel and Gandhi grew close to each other, and the two developed a close bond of affection, trust, and frankness. Their mutual relationship could be described as that of an elder brother (Gandhi) and his younger brother (Patel). Despite having arguments with Gandhi, Patel respected his instincts and leadership. In prison, the two discussed national and social issues, read Hindu epics, and cracked jokes. Gandhi taught Patel Sanskrit. Gandhi's secretary, Mahadev Desai, kept detailed records of conversations between Gandhi and Patel.[34] When Gandhi embarked on a fast-unto-death protesting the separate electorates allocated for untouchables, Patel looked after Gandhi closely and himself refrained from partaking of food.[35] Patel was later moved to a jail in Nasik, and refused a British offer for a brief release to attend the cremation of his brother Vithalbhai, who had died in October 1933. He was finally released in July of 1934.[citation needed]

Patel's position at the highest level in the Congress was largely connected with his role from 1934 onwards (when the Congress abandoned its boycott of elections) in the party organisation. Based at an apartment in Mumbai, he became the Congress's main fundraiser and chairman of its Central Parliamentary Board, playing the leading role in selecting and financing candidates for the 1934 elections to the Central Legislative Assembly in New Delhi and for the provincial elections of 1936.[36] In addition to collecting funds and selecting candidates, he also determined the Congress's stance on issues and opponents.[37] Not contesting a seat for himself, Patel nevertheless guided Congressmen elected in the provinces and at the national level. In 1935 Patel underwent surgery for haemorrhoids, yet continued to direct efforts against the plague in Bardoli and again when a drought struck Gujarat in 1939. Patel guided the Congress ministries that had won power across India with the aim of preserving party discipline – Patel feared that the British would take advantage of opportunities to create conflict among elected Congressmen, and he did not want the party to be distracted from the goal of complete independence.[38] Patel clashed with Nehru, opposing declarations of the adoption of socialism at the 1936 Congress session, which he believed was a diversion from the main goal of achieving independence. In 1938 Patel organised rank and file opposition to the attempts of then-Congress president Subhas Chandra Bose to move away from Gandhi's principles of non-violent resistance. Patel saw Bose as wanting more power over the party. He led senior Congress leaders in a protest that resulted in Bose's resignation. But criticism arose from Bose's supporters, socialists, and other Congressmen that Patel himself was acting in an authoritarian manner in his defence of Gandhi's authority.[citation needed]

Legal Battle with Subhas Chandra Bose[edit]

Patel's elder brother Vithalbhai Patel, died in Geneva on October 22, 1933.[39]

Vithalbhai and Bose had been highly critical of Gandhi’s leadership during their travels in Europe. "By the time Vithalbhai died in October 1932, Bose had become his primary caregiver. On his deathbed he left a will of sorts, bequeathing three-quarters of his money to Bose to use in promoting India’s cause in other countries. When Patel saw a copy of the letter in which his brother had left a majority of his estate to Bose, he asked a series of questions: Why was the letter not attested by a doctor? Had the original paper been preserved? Why were the witnesses to that letter all men from Bengal and none of the many other veteran freedom activists and supporters of the Congress who had been present at Geneva where Vithalbhai had died? Patel may even have doubted the veracity of the signature on the document. The case went to the court and after a legal battle that lasted more than a year, the courts judged that Vithalbhai’s estate could only be inherited by his legal heirs, that is, his family. Patel promptly handed the money over to the Vithalbhai Memorial Trust."[40][page needed]

Quit India[edit]

On the outbreak of World War II, Patel supported Nehru's decision to withdraw the Congress from central and provincial legislatures, contrary to Gandhi's advice, as well as an initiative by senior leader Chakravarthi Rajagopalachari to offer Congress's full support to Britain if it promised Indian independence at the end of the war and installed a democratic government right away. Gandhi had refused to support Britain on the grounds of his moral opposition to war, while Subhash Chandra Bose was in militant opposition to the British. The British rejected Rajagopalachari's initiative, and Patel embraced Gandhi's leadership again.[41] He participated in Gandhi's call for individual disobedience, and was arrested in 1940 and imprisoned for nine months. He also opposed the proposals of the Cripps' mission in 1942. Patel lost more than twenty pounds during his period in jail.[citation needed]

While Nehru, Rajagopalachari, and Maulana Azad initially criticised Gandhi's proposal for an all-out campaign of civil disobedience to force the British to quit India, Patel was its most fervent supporter. Arguing that the British would retreat from India as they had from Singapore and Burma, Patel urged that the campaign start without any delay.[42] Though feeling that the British would not leave immediately, Patel favoured an all-out rebellion that would galvanise the Indian people, who had been divided in their response to the war, In Patel's view, such a rebellion would force the British to concede that continuation of colonial rule had no support in India, and thus speed the transfer of power to Indians.[43] Believing strongly in the need for revolt, Patel stated his intention to resign from the Congress if the revolt were not approved.[44] Gandhi strongly pressured the All India Congress Committee to approve an all-out campaign of civil disobedience, and the AICC approved the campaign on 7 August 1942. Though Patel's health had suffered during his stint in jail, he gave emotional speeches to large crowds across India,[45] asking them to refuse to pay taxes and to participate in civil disobedience, mass protests, and a shutdown of all civil services. He raised funds and prepared a second tier of command as a precaution against the arrest of national leaders.[46] Patel made a climactic speech to more than 100,000 people gathered at Gowalia Tank in Bombay (Mumbai) on 7 August:

Historians believe that Patel's speech was instrumental in electrifying nationalists, who up to then had been skeptical of the proposed rebellion. Patel's organising work in this period is credited by historians with ensuring the success of the rebellion across India.[48] Patel was arrested on 9 August and was imprisoned with the entire Congress Working Committee from 1942 to 1945 at the fort in Ahmednagar. Here he spun cloth, played bridge, read a large number of books, took long walks, and practised gardening. He also provided emotional support to his colleagues while awaiting news and developments from the outside.[49] Patel was deeply pained at the news of the deaths of Mahadev Desai and Kasturba Gandhi later that year.[50] But Patel wrote in a letter to his daughter that he and his colleagues were experiencing "fullest peace" for having done "their duty".[51] Even though other political parties had opposed the struggle and the British had employed ruthless means of suppression, the Quit India movement was "by far the most serious rebellion since that of 1857", as the viceroy cabled to Winston Churchill. More than 100,000 people were arrested and many were killed in violent struggles with the police. Strikes, protests, and other revolutionary activities had broken out across India.[52]When Patel was released on 15 June 1945, he realised that the British were preparing proposals to transfer power to India.[citation needed]

Integration after Independence and role of Gandhi[edit]

As the first Home Minister, Patel played the key role in the integration of the princely states into the Indian federation.[53] In the elections, the Congress won a large majority of the elected seats, dominating the Hindu electorate. But the Muslim League led by Muhammad Ali Jinnah won a large majority of Muslim electorate seats. The League had resolved in 1940 to demand Pakistan – an independent state for Muslims – and was a fierce critic of the Congress. The Congress formed governments in all provinces save Sindh, Punjab, and Bengal, where it entered into coalitions with other parties.

Cabinet mission and partition[edit]

When the British mission proposed two plans for transfer of power, there was considerable opposition within the Congress to both. The plan of 16 May 1946 proposed a loose federation with extensive provincial autonomy, and the "grouping" of provinces based on religious-majority. The plan of 16 May 1946 proposed the partition of India on religious lines, with over 565 princely states free to choose between independence or accession to either dominion. The League approved both plans while the Congress flatly rejected the proposal of 16 May. Gandhi criticised the 16 May proposal as being inherently divisive, but Patel, realising that rejecting the proposal would mean that only the League would be invited to form a government, lobbied the Congress Working Committee hard to give its assent to the 16 May proposal. Patel engaged the British envoys Sir Stafford Cripps and Lord Pethick-Lawrence and obtained an assurance that the "grouping" clause would not be given practical force, Patel converted Jawaharlal Nehru, Rajendra Prasad, and Rajagopalachari to accept the plan. When the League retracted its approval of the 16 May plan, the viceroy Lord Wavell invited the Congress to form the government. Under Nehru, who was styled the "Vice President of the Viceroy's Executive Council", Patel took charge of the departments of home affairs and information and broadcasting. He moved into a government house on Aurangzeb Road in Delhi, which would be his home until his death in 1950.[54]

Vallabhbhai Patel was one of the first Congress leaders to accept the partition of India as a solution to the rising Muslim separatist movement led by Muhammad Ali Jinnah. He had been outraged by Jinnah's Direct Action campaign, which had provoked communal violence across India, and by the viceroy's vetoes of his home department's plans to stop the violence on the grounds of constitutionality. Patel severely criticised the viceroy's induction of League ministers into the government, and the revalidation of the grouping scheme by the British without Congress's approval. Although further outraged at the League's boycott of the assembly and non-acceptance of the plan of 16 May despite entering government, he was also aware that Jinnah did enjoy popular support amongst Muslims, and that an open conflict between him and the nationalists could degenerate into a Hindu-Muslim civil war of disastrous consequences. The continuation of a divided and weak central government would, in Patel's mind, result in the wider fragmentation of India by encouraging more than 600 princely states towards independence.[55] In December 1946 and January 1947, Patel worked with civil servant V. P. Menon on the latter's suggestion for a separate dominion of Pakistan created out of Muslim-majority provinces. Communal violence in Bengal and Punjab in January and March 1947 further convinced Patel of the soundness of partition. Patel, a fierce critic of Jinnah's demand that the Hindu-majority areas of Punjab and Bengal be included in a Muslim state, obtained the partition of those provinces, thus blocking any possibility of their inclusion in Pakistan. Patel's decisiveness on the partition of Punjab and Bengal had won him many supporters and admirers amongst the Indian public, which had tired of the League's tactics, but he was criticised by Gandhi, Nehru, secular Muslims, and socialists for a perceived eagerness to do so. When Lord Louis Mountbatten formally proposed the plan on 3 June 1947, Patel gave his approval and lobbied Nehru and other Congress leaders to accept the proposal. Knowing Gandhi's deep anguish regarding proposals of partition, Patel engaged him in frank discussion in private meetings over what he saw as the practical unworkability of any Congress–League coalition, the rising violence, and the threat of civil war. At the All India Congress Committee meeting called to vote on the proposal, Patel said:

After Gandhi rejected and Congress approved – the plan, Patel represented India on the Partition Council,[57][58] where he oversaw the division of public assets, and selected the Indian council of ministers with Nehru.[59] However, neither Patel nor any other Indian leader had foreseen the intense violence and population transfer that would take place with partition. Patel took the lead in organising relief and emergency supplies, establishing refugee camps, and visiting the border areas with Pakistani leaders to encourage peace. Despite these efforts, the death toll is estimated at between 500,000 and 1 million people.[60] The estimated number of refugees in both countries exceeds 15 million.[61] Understanding that Delhi and Punjab policemen, accused of organising attacks on Muslims, were personally affected by the tragedies of partition, Patel called out the Indian Army with South Indian regiments to restore order, imposing strict curfews and shoot-at-sight orders. Visiting the Nizamuddin Auliya Dargah area in Delhi, where thousands of Delhi Muslims feared attacks, he prayed at the shrine, visited the people, and reinforced the presence of police. He suppressed from the press reports of atrocities in Pakistan against Hindus and Sikhs to prevent retaliatory violence. Establishing the Delhi Emergency Committee to restore order and organising relief efforts for refugees in the capital, Patel publicly warned officials against partiality and neglect. When reports reached Patel that large groups of Sikhs were preparing to attack Muslim convoys heading for Pakistan, Patel hurried to Amritsar and met Sikh and Hindu leaders. Arguing that attacking helpless people was cowardly and dishonourable, Patel emphasised that Sikh actions would result in further attacks against Hindus and Sikhs in Pakistan. He assured the community leaders that if they worked to establish peace and order and guarantee the safety of Muslims, the Indian government would react forcefully to any failures of Pakistan to do the same. Additionally, Patel addressed a massive crowd of approximately 200,000 refugees who had surrounded his car after the meetings:

Following his dialogue with community leaders and his speech, no further attacks occurred against Muslim refugees, and a wider peace and order was soon re-established over the entire area. However, Patel was criticised by Nehru, secular Muslims, and Gandhi over his alleged wish to see Muslims from other parts of India depart. While Patel vehemently denied such allegations, the acrimony with Maulana Azad and other secular Muslim leaders increased when Patel refused to dismiss Delhi's Sikh police commissioner, who was accused of discrimination. Hindu and Sikh leaders also accused Patel and other leaders of not taking Pakistan sufficiently to task over the attacks on their communities there, and Muslim leaders further criticised him for allegedly neglecting the needs of Muslims leaving for Pakistan, and concentrating resources for incoming Hindu and Sikh refugees. Patel clashed with Nehru and Azad over the allocation of houses in Delhi vacated by Muslims leaving for Pakistan; Nehru and Azad desired to allocate them for displaced Muslims, while Patel argued that no government professing secularism must make such exclusions. However, Patel was publicly defended by Gandhi and received widespread admiration and support for speaking frankly on communal issues and acting decisively and resourcefully to quell disorder and violence.[63]

Political integration of India[edit]

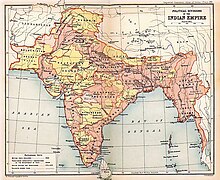

Patel took charge of the integration of the princely states into India.[53] This achievement formed the cornerstone of Patel's popularity in the post-independence era. Even today he is remembered as the man who united India. He is, in this regard, compared to Otto von Bismarck of Germany, who did the same thing in the 1860s. Under the plan of 3 June, more than 562 princely states were given the option of joining either India or Pakistan, or choosing independence. Indian nationalists and large segments of the public feared that if these states did not accede, most of the people and territory would be fragmented. The Congress as well as senior British officials considered Patel the best man for the task of achieving conquest of the princely states by the Indian dominion. Gandhi had said to Patel, "[T]he problem of the States is so difficult that you alone can solve it".[64] Patel was considered a statesman of integrity with the practical acumen and resolve to accomplish a monumental task. He asked V. P. Menon, a senior civil servant with whom he had worked on the partition of India, to become his right-hand man as chief secretary of the States Ministry. On 6 May 1947, Patel began lobbying the princes, attempting to make them receptive towards dialogue with the future government and forestall potential conflicts. Patel used social meetings and unofficial surroundings to engage most of the monarchs, inviting them to lunch and tea at his home in Delhi. At these meetings, Patel explained that there was no inherent conflict between the Congress and the princely order. Patel invoked the patriotism of India's monarchs, asking them to join in the independence of their nation and act as responsible rulers who cared about the future of their people. He persuaded the princes of 565 states of the impossibility of independence from the Indian republic, especially in the presence of growing opposition from their subjects. He proposed favourable terms for the merger, including the creation of privy purses for the rulers' descendants. While encouraging the rulers to act out of patriotism, Patel did not rule out force. Stressing that the princes would need to accede to India in good faith, he set a deadline of 15 August 1947 for them to sign the instrument of accession document. All but three of the states willingly merged into the Indian union; only Jammu and Kashmir, Junagadh, and Hyderabad did not fall into his basket.[65]

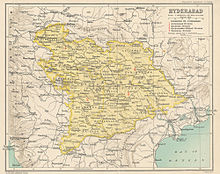

Junagadh was especially important to Patel, since it was in his home state of Gujarat. It was also important because in this Kathiawar district was the ultra-rich Somnath temple (which in the 11th century had been plundered by Mahmud of Ghazni, who damaged the temple and its idols to rob it of its riches, including emeralds, diamonds, and gold). Under pressure from Sir Shah Nawaz Bhutto, the Nawab had acceded to Pakistan. It was, however, quite far from Pakistan, and 80% of its population was Hindu. Patel combined diplomacy with force, demanding that Pakistan annul the accession, and that the Nawab accede to India. He sent the Army to occupy three principalities of Junagadh to show his resolve. Following widespread protests and the formation of a civil government, or Aarzi Hukumat, both Bhutto and the Nawab fled to Karachi, and under Patel's orders the Indian Army and police units marched into the state. A plebiscite organised later produced a 99.5% vote for merger with India.[66] In a speech at the Bahauddin College in Junagadh following the latter's take-over, Patel emphasised his feeling of urgency on Hyderabad, which he felt was more vital to India than Kashmir:

Hyderabad was the largest of the princely states, and it included parts of present-day Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and Maharashtra states. Its ruler, the Nizam Osman Ali Khan, was a Muslim, although over 80% of its people were Hindu. The Nizam sought independence or accession with Pakistan. Muslim forces loyal to Nizam, called the Razakars, under Qasim Razvi, pressed the Nizam to hold out against India, while organising attacks on people on Indian soil. Even though a Standstill Agreement was signed due to the desperate efforts of Lord Mountbatten to avoid a war, the Nizam rejected deals and changed his positions.[67] In September 1948 Patel emphasised in Cabinet meetings that India should talk no more, and reconciled Nehru and the Governor-General, Chakravarti Rajgopalachari, to military action. Following preparations, Patel ordered the Indian Army to invade Hyderabad (in his capacity as Acting Prime Minister) when Nehru was touring Europe.[68] The action was termed Operation Polo, and thousands of Razakar forces were killed, but Hyderabad was forcefully secured and integrated into the Indian Union.[69] The main aim of Mountbatten and Nehru in avoiding a forced annexation was to prevent an outbreak of Hindu–Muslim violence. Patel insisted that if Hyderabad were allowed to continue as an independent nation enclave surrounded by India, the prestige of the government would fall, and then neither Hindus nor Muslims would feel secure in its realm. After defeating Nizam, Patel retained him as the ceremonial chief of state, and held talks with him.[70]There were 562 princely states in India which Sardar Patel conquered.

Leading India[edit]

The Governor-General of India, Chakravarti Rajagopalachari, along with Nehru and Patel, formed the "triumvirate" that ruled India from 1948 to 1950. Prime Minister Nehru was intensely popular with the masses, but Patel enjoyed the loyalty and the faith of rank and file Congressmen, state leaders, and India's civil servants. Patel was a senior leader in the Constituent Assembly of India and was responsible in large measure for shaping India's constitution.[71]

Patel was the chairman of the committees responsible for minorities, tribal and excluded areas, fundamental rights, and provincial constitutions. Patel piloted a model constitution for the provinces in the Assembly, which contained limited powers for the state governor, who would defer to the president – he clarified it was not the intention to let the governor exercise power that could impede an elected government.[71] He worked closely with Muslim leaders to end separate electorates and the more potent demand for reservation of seats for minorities.[72] His intervention was key to the passage of two articles that protected civil servants from political involvement and guaranteed their terms and privileges.[71] He was also instrumental in the founding the Indian Administrative Service and the Indian Police Service, and for his defence of Indian civil servants from political attack; he is known as the "patron saint" of India's services. When a delegation of Gujarati farmers came to him citing their inability to send their milk production to the markets without being fleeced by intermediaries, Patel exhorted them to organise the processing and sale of milk by themselves, and guided them to create the Kaira District Co-operative Milk Producers' Union Limited, which preceded the Amul milk products brand. Patel also pledged the reconstruction of the ancient but dilapidated Somnath Temple in Saurashtra. He oversaw the restoration work and the creation of a public trust, and pledged to dedicate the temple upon the completion of work (the work was completed after his death and the temple was inaugurated by the first President of India, Dr. Rajendra Prasad).

When the Pakistani invasion of Kashmir began in September 1947, Patel immediately wanted to send troops into Kashmir. But, agreeing with Nehru and Mountbatten, he waited until Kashmir's monarch had acceded to India. Patel then oversaw India's military operations to secure Srinagar and the Baramulla Pass, and the forces retrieved much territory from the invaders. Patel, along with Defence Minister Baldev Singh, administered the entire military effort, arranging for troops from different parts of India to be rushed to Kashmir and for a major military road connecting Srinagar to Pathankot to be built in six months.[73] Patel strongly advised Nehru against going for arbitration to the United Nations, insisting that Pakistan had been wrong to support the invasion and the accession to India was valid. He did not want foreign interference in a bilateral affair. Patel opposed the release of Rs. 550 million to the Government of Pakistan, convinced that the money would go to finance the war against India in Kashmir. The Cabinet had approved his point but it was reversed when Gandhi, who feared an intensifying rivalry and further communal violence, went on a fast-unto-death to obtain the release. Patel, though not estranged from Gandhi, was deeply hurt at the rejection of his counsel and a Cabinet decision.[74]

In 1949 a crisis arose when the number of Hindu refugees entering West Bengal, Assam, and Tripura from East Pakistan climbed to over 800,000. The refugees in many cases were being forcibly evicted by Pakistani authorities, and were victims of intimidation and violence.[75] Nehru invited Liaquat Ali Khan, Prime Minister of Pakistan, to find a peaceful solution. Despite his aversion, Patel reluctantly met Khan and discussed the matter. Patel strongly criticised Nehru's plan to sign a pact that would create minority commissions in both countries and pledge both India and Pakistan to a commitment to protect each other's minorities.[76] Syama Prasad Mookerjee and K. C. Neogy, two Bengali ministers, resigned, and Nehru was intensely criticised in West Bengal for allegedly appeasing Pakistan. The pact was immediately in jeopardy. Patel, however, publicly came to Nehru's aid. He gave emotional speeches to members of Parliament, and the people of West Bengal, and spoke with scores of delegations of Congressmen, Hindus, Muslims, and other public interest groups, persuading them to give peace a final effort.[77]

In April 2015 the Government of India declassified surveillance reports suggesting that Patel, while Home Minister, and Nehru were among officials involved in alleged government-authorised spying on the family of Subhas Chandra Bose.[78]

Father of All India Services[edit]

There is no alternative to this administrative system... The Union will go, you will not have a united India if you do not have good All-India Service which has the independence to speak out its mind, which has sense of security that you will standby your work... If you do not adopt this course, then do not follow the present Constitution. Substitute something else... these people are the instrument. Remove them and I see nothing but a picture of chaos all over the country.

Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, in Constituent Assembly discussing the role of All India Services.[79][80][81]

He was also instrumental in the creation of the All India Services which he described as the country’s "Steel Frame". In his address to the probationers of these services, he asked them to be guided by the spirit of service in day-to-day administration. He reminded them that the ICS was no longer neither Imperial, nor civil, nor imbued with any spirit of service after Independence. His exhortation to the probationers to maintain utmost impartiality and incorruptibility of administration is as relevant today as it was then. "A civil servant cannot afford to, and must not, take part in politics. Nor must he involve himself in communal wrangles. To depart from the path of rectitude in either of these respects is to debase public service and to lower its dignity," he had cautioned them on 21 April 1947.[82]

He, more than anyone else in post-independence India, realized the crucial role that civil services play in administering a country, in not merely maintaining law and order, but running the institutions that provide the binding cement to a society. He, more than any other contemporary of his, was aware of the needs of a sound, stable administrative structure as the lynchpin of a functioning polity. The present-day all-India administrative services owe their origin to the man’s sagacity and thus he is regarded as Father of modern All India Services.[83]

Gandhi's death and relations with Nehru[edit]

Rajmohan Gandhi, in his book writes that Nehru was focused on maintaining religious harmony, casting an independent foreign policy, and constructing a technological and industrial base, while Patel focused on getting the princely states to join the Indian Union, modernising the administrative services, and constructing a cross-party consensus on the significant elements of the Constitution.[84]

Patel was intensely loyal to Gandhi, and both he and Nehru looked to him to arbitrate disputes. However, Nehru and Patel sparred over national issues.[85] When Nehru asserted control over Kashmir policy, Patel objected to Nehru's sidelining his home ministry's officials.[86] Nehru was offended by Patel's decision-making regarding the states' integration, having consulted neither him nor the Cabinet. Patel asked Gandhi to relieve him of his obligation to serve, believing that an open political battle would hurt India. After much personal deliberation and contrary to Patel's prediction, Gandhi on 30 January 1948 told Patel not to leave the government. A free India, according to Gandhi, needed both Patel and Nehru. Patel was the last man to privately talk with Gandhi, who was assassinated just minutes after Patel's departure.[87] At Gandhi's wake, Nehru and Patel embraced each other and addressed the nation together. Patel gave solace to many associates and friends and immediately moved to forestall any possible violence.[88] Within two months of Gandhi's death, Patel suffered a major heart attack; the timely action of his daughter, his secretary, and a nurse saved Patel's life. Speaking later, Patel attributed the attack to the "grief bottled up" due to Gandhi's death.[89]

Criticism arose from the media and other politicians that Patel's home ministry had failed to protect Gandhi. Emotionally exhausted, Patel tendered a letter of resignation, offering to leave the government. Patel's secretary persuaded him to withhold the letter, seeing it as fodder for Patel's political enemies and political conflict in India.[90] However, Nehru sent Patel a letter dismissing any question of personal differences or desire for Patel's ouster. He reminded Patel of their 30-year partnership in the independence struggle and asserted that after Gandhi's death, it was especially wrong for them to quarrel. Nehru, Rajagopalachari, and other Congressmen publicly defended Patel. Moved, Patel publicly endorsed Nehru's leadership and refuted any suggestion of discord, and dispelled any notion that he sought to be prime minister.[90]

Nehru gave Patel a free hand in integrating the princely states into India.[53] Though the two committed themselves to joint leadership and non-interference in Congress party affairs, they sometimes would criticise each other in matters of policy, clashing on the issues of Hyderabad's integration and UN mediation in Kashmir. Nehru declined Patel's counsel on sending assistance to Tibet after its 1950 invasion by the People's Republic of China and on ejecting the Portuguese from Goa by military force.[91] Nehru also tried to scuttle Patel's plan with regards to Hyderabad. During a meeting, according to the then civil servant MKK Nair in his book With No Ill Feeling to Anybody, Nehru shouted and accused Patel of being a communalist.[citation needed] Patel also one on occasion called Nehru, a Maulana, for appeasing Muslims.[92]

When Nehru pressured Rajendra Prasad to decline a nomination to become the first President of India in 1950 in favour of Rajagopalachari, he angered the party, which felt Nehru was attempting to impose his will. Nehru sought Patel's help in winning the party over, but Patel declined, and Prasad was duly elected. Nehru opposed the 1950 Congress presidential candidate Purushottam Das Tandon, a conservative Hindu leader, endorsing Jivatram Kripalani instead and threatening to resign if Tandon was elected. Patel rejected Nehru's views and endorsed Tandon in Gujarat, where Kripalani received not one vote despite hailing from that state himself.[93] Patel believed Nehru had to understand that his will was not law with the Congress, but he personally discouraged Nehru from resigning after the latter felt that the party had no confidence in him.[94]

On 29 March 1949 authorities lost radio contact with a plane carrying Patel, his daughter Maniben, and the Maharaja of Patiala. Engine failure caused the pilot to make an emergency landing in a desert area in Rajasthan. With all passengers safe, Patel and others tracked down a nearby village and local officials. When Patel returned to Delhi, thousands of Congressmen gave him a resounding welcome. In Parliament, MPs gave a long standing ovation to Patel, stopping proceedings for half an hour.[95]

In his twilight years, Patel was honoured by members of Parliament. He was awarded honorary doctorates of law by Nagpur University, the University of Allahabad and Banaras Hindu University in November 1948, subsequently receiving honorary doctorates from Osmania University in February 1949 and from Punjab University in March 1949.[96][97] Previously, Patel had been featured on the cover page of the January 1947 issue of Time magazine.[98]

Death[edit]

Patel's health declined rapidly through the summer of 1950. He later began coughing blood, whereupon Maniben began limiting her meetings and working hours and arranged for a personalised medical staff to begin attending to Patel. The Chief Minister of West Bengaland doctor Bidhan Roy heard Patel make jokes about his impending end, and in a private meeting Patel frankly admitted to his ministerial colleague N. V. Gadgil that he was not going to live much longer. Patel's health worsened after 2 November, when he began losing consciousness frequently and was confined to his bed. He was flown to Bombay (now Mumbai) on 12 December on advice from Dr Roy, to recuperate as his condition was deemed critical.[99] Nehru, Rajagopalchari, Rajendra Prasad, and Menon all came to see him off at the airport in Delhi. Patel was extremely weak and had to be carried onto the aircraft in a chair. In Bombay, large crowds gathered at Santacruz Airport to greet him. To spare him from this stress, the aircraft landed at Juhu Aerodrome, where Chief Minister B. G. Kher and Morarji Desai were present to receive him with a car belonging to the Governor of Bombay that took Vallabhbhai to Birla House.[100][101]

After suffering a massive heart attack (his second), Patel died on 15 December 1950 at Birla House in Bombay.[102] In an unprecedented and unrepeated gesture, on the day after his death more than 1,500 officers of India's civil and police services congregated to mourn at Patel's residence in Delhi and pledged "complete loyalty and unremitting zeal" in India's service.[103] Numerous governments and world leaders sent messages of condolence upon Patel's death, including Trygve Lie, the Secretary-General of the United Nations, President Sukarno of Indonesia, Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan of Pakistan and Prime Minister Clement Attlee of the United Kingdom.[104]

In homage to Patel, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru declared a week of national mourning.[105] Patel's cremation was planned at Girgaum Chowpatty, but this was changed to Sonapur (now Marine Lines) when his daughter conveyed that it was his wish to be cremated like a common man in the same place as his wife and brother were earlier cremated. K.M Munshi wrote in his book that after Patel's death Nehru ‘issued a direction to the Ministers and the Secretaries not to go to Bombay to attend the funeral. Jawaharlal also requested Dr. Rajendra Prasad not to go to Bombay; it was a strange request to which Rajendra Prasad did not accede.’.[106][107] His cremation in Sonapur in Bombay was attended by a crowd of one million including Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, Rajagopalachari and President Rajendra Prasad.[101][108][109]

Reception[edit]

During his lifetime, Vallabhbhai Patel received criticism for an alleged bias against Muslims during the time of Partition. He was criticised by Maulana Azad and others for readily supporting partition.[110] Guha says that, during the Partition, Nehru wanted the government to make the Muslims stay back and feel secure in India while Patel was inclined to place that responsibility on the individuals themselves. Patel also told Nehru that the minority also had to remove the doubts that were entertained about their loyalty based on their past association with the demand of Pakistan.[111] However, Patel successfully prevented attacks upon a train of Muslim refugees leaving India.[112] In September 1947 he was said to have had ten thousand Muslims sheltered safely in the Red Fort and had free kitchens opened for them during the communal violence.[113] Patel was also said to be more forgiving of Indian nationalism and harsher on Pakistan.[114] He exposed a riot plot, confiscated a large haul of weapons from the Delhi Jumma Masjid, and had a few plotters killed by the police, but his approach was said to have been harsh.[113]

Patel was also criticised by supporters of Subhas Chandra Bose for acting coercively to put down politicians not supportive of Gandhi.[115] Socialist politicians such as Jaya Prakash Narayan and Asoka Mehta criticised him for his personal proximity to Indian industrialists such as the Birla and Sarabhai families. It is said that Patel was friendly towards capitalists while Nehru believed in the state controlling the economy.[114] Also, Patel was more inclined to support the West in the emerging Cold War.[114]

Nehru and Patel[edit]

Patel had long been the rival of Nehru for party leadership, but Nehru usually prevailed over the older man, who died in 1950.[85] Subsequently, J. R. D. Tata, the Industrialist, Maulana Azad and several others expressed the opinion that Patel would have made a better Prime Minister for India than Nehru.[116] These Patel admirers and Nehru's critics cite Nehru's belated embrace of Patel's advice regarding the UN and Kashmir and the integration of Goa by military action and Nehru's rejection of Patel's advice on China.[117] Proponents of free enterprise cite the failings of Nehru's socialist policies as opposed to Patel's defence of property rights and his mentorship of what was to be later known as the Amul co-operative project.[118][119] However, A. G. Noorani, in comparing Nehru and Patel, writes that Nehru had a broader understanding of the world than Patel.[120]

Historian Rajmohan Gandhi argues:

- Patel the realist was home minister and deputy premier, Nehru the visionary was premier and foreign minister. The two constituted a formidable pair. Patel represented Indian nationalism’s Hindu face, Nehru India’s secular and also global face. Their partnership, necessary and fruitful for the country, was a solemn commitment that each made to the other.[121]

Legacy[edit]

In his eulogy, delivered the day after Patel's death, Sir Girija Shankar Bajpai, the Secretary-General of the Ministry of External Affairs, paid tribute to "a great patriot, a great administrator and a great man. Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel was all three, a rare combination in any historic epoch and in any country."[96] Bajpai lauded Patel for his achievements as a patriot and as an administrator, notably his vital role in securing India's stability in the aftermath of Independence and Partition:

Among Patel's surviving family, Maniben Patel lived in a flat in Mumbai for the rest of her life following her father's death; she often led the work of the Sardar Patel Memorial Trust, which organises the prestigious annual Sardar Patel Memorial Lectures, and other charitable organisations. Dahyabhai Patel was a businessman who was elected to serve in the Lok Sabha (the lower house of the Indian Parliament) as an MP in the 1960s.[122]

For many decades after his death, there was a perceived lack of effort from the Government of India, the national media, and the Congress party regarding commemoration of Patel's life and work.[123] Patel was posthumously awarded the Bharat Ratna, India's highest civilian honour, in 1991.[124] It was announced in 2014 that his birthday, 31 October, would become an annual national celebration known as Rashtriya Ekta Diwas (National Unity Day).[125] In 2012, Patel was ranked third in Outlook India's poll of the Greatest Indian.[126]

Patel's family home in Karamsad is preserved in his memory.[127] The Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel National Memorial in Ahmedabad was established in 1980 at the Moti Shahi Mahal. It comprises a museum, a gallery of portraits and historical pictures, and a library containing important documents and books associated with Patel and his life. Amongst the exhibits are many of Patel's personal effects and relics from various periods of his personal and political life.[128]

Patel is the namesake of many public institutions in India. A major initiative to build dams, canals, and hydroelectric power plants in the Narmada river valley to provide a tri-state area with drinking water and electricity and to increase agricultural production was named the Sardar Sarovar. Patel is also the namesake of the Sardar Vallabhbhai National Institute of Technology in Surat, Sardar Patel University, Sardar Patel High School, and the Sardar Patel Vidyalaya, which are among the nation's premier institutions. India's national police training academy is also named after him.[129]

The international airport of Ahmedabad is named after him. Also the international cricket stadium of Ahmedabad (also known as the Motera Stadium) is named after him. A national cricket stadium in Navrangpura, Ahmedabad, used for national matches and events, is also named after him. The chief outer ring road encircling Ahmedabad is named S P Ring Road. The Gujarat government's institution for training government functionaries is named Sardar Patel Institute of Public Administration.[citation needed]

Rashtriya Ekta Diwas[edit]

Rashtriya Ekta Diwas (National Unity Day) was introduced by the Government of India and inaugurated by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2014. The intent is to pay tribute to Patel, who was instrumental in keeping India united. It is to be celebrated on 31 October every year as annual commemoration of the birthday of the Iron Man of India Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, one of the founding leaders of Republic of India. The official statement for Rashtriya Ekta Diwas by the Home Ministry of India cites that the National Unity Day "will provide an opportunity to re-affirm the inherent strength and resilience of our nation to withstand the actual and potential threats to the unity, integrity and security of our country."[130]

National Unity Day celebrates the birthday of Patel because, during his term as Home Minister of India, he is credited for the integration of over 550 independent princely states into India from 1947–49 by Independence Act (1947). He is known as the "Bismarck[a] of India".[131][132] The celebration is complemented with the speech of Prime Minister of India followed by the "Run for Unity".[8] The theme for 2016 celebrations was "Integration of India".[133]

Statue of Unity[edit]

The Statue of Unity is a monument dedicated to Patel, located in the Indian state of Gujarat, facing the Narmada Dam, 3.2 km away from Sadhu Bet near Vadodara. At the height of 182 metres (597 feet), it is the world's tallest statue, exceeding the Spring Temple Buddha by 54 meters.[134] This statue and related structures are spread over 20000 square meters and are surrounded by an artificial lake spread across 12 km and cost an estimated 29.8 billion rupees ($430m).[134] It was inaugurated by India's Prime Minister Narendra Modi on 31 October 2018, the 143rd anniversary of Patel's birth.

2.Subhas Chandra Bose

|

Subhas Chandra Bose

| |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| In office 21 October 1943 – 18 August 1945 | |

| Preceded by | Office created |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| President of the Indian National Congress | |

| In office 1938–1939 | |

| Preceded by | Jawaharlal Nehru |

| Succeeded by | Rajendra Prasad |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Subhas Chandra Bose

23 January 1897 Cuttack, Bengal Presidency, British India (present-day Odisha, India) |

| Died | 18 August 1945 (aged 48) Taihoku, Japanese Taiwan(present-day Taipei, Taiwan) |

| Political party |

|

| Spouse(s) | Emilie Schenkl |

| Children | Anita Bose Pfaff |

| Mother | Prabhavati Dutt |

| Father | Janakinath Bose |

| Education | |

| Alma mater | |

| Known for | Indian nationalism |

| Signature | |

Subhas Chandra Bose (23 January 1897 – 18 August 1945)[3][b] was an Indian nationalist whose defiant patriotism made him a hero in India,[4][c][5][d][6][e] but whose attempt during World War II to rid India of British rule with the help of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan left a troubled legacy.[7][f][8][g][4][h] The honorific Netaji (Hindustani: "Respected Leader"), first applied in early 1942 to Bose in Germany by the Indian soldiers of the Indische Legion and by the German and Indian officials in the Special Bureau for India in Berlin, was later used throughout India.[9][i]

Bose had been a leader of the younger, radical, wing of the Indian National Congress in the late 1920s and 1930s, rising to become Congress President in 1938 and 1939.[10][j] However, he was ousted from Congress leadership positions in 1939 following differences with Mahatma Gandhi and the Congress high command.[11] He was subsequently placed under house arrest by the British before escaping from India in 1940.[12]

Bose arrived in Germany in April 1941, where the leadership offered unexpected, if sometimes ambivalent, sympathy for the cause of India's independence, contrasting starkly with its attitudes towards other colonised peoples and ethnic communities.[13][14] In November 1941, with German funds, a Free India Centre was set up in Berlin, and soon a Free India Radio, on which Bose broadcast nightly. A 3,000-strong Free India Legion, comprising Indians captured by Erwin Rommel's Afrika Korps, was also formed to aid in a possible future German land invasion of India.[15] By spring 1942, in light of Japanese victories in southeast Asia and changing German priorities, a German invasion of India became untenable, and Bose became keen to move to southeast Asia.[16] Adolf Hitler, during his only meeting with Bose in late May 1942, suggested the same, and offered to arrange for a submarine.[17] During this time Bose also became a father; his wife, [18] or companion,[19][k] Emilie Schenkl, whom he had met in 1934, gave birth to a baby girl in November 1942.[18][13] Identifying strongly with the Axis powers, and no longer apologetically, Bose boarded a German submarine in February 1943.[20][21] In Madagascar, he was transferred to a Japanese submarine from which he disembarked in Japanese-held Sumatra in May 1943.[20]

With Japanese support, Bose revamped the Indian National Army (INA), then composed of Indian soldiers of the British Indian army who had been captured in the Battle of Singapore.[22] To these, after Bose's arrival, were added enlisting Indian civilians in Malaya and Singapore. The Japanese had come to support a number of puppet and provisional governments in the captured regions, such as those in Burma, the Philippines and Manchukuo. Before long the Provisional Government of Free India, presided by Bose, was formed in the Japanese-occupied Andaman and Nicobar Islands.[22][1][l] Bose had great drive and charisma—creating popular Indian slogans, such as "Jai Hind,"—and the INA under Bose was a model of diversity by region, ethnicity, religion, and even gender. However, Bose was regarded by the Japanese as being militarily unskilled,[23][m] and his military effort was short-lived. In late 1944 and early 1945 the British Indian Army first halted and then devastatingly reversed the Japanese attack on India. Almost half the Japanese forces and fully half the participating INA contingent were killed.[24][n] The INA was driven down the Malay Peninsula, and surrendered with the recapture of Singapore. Bose had earlier chosen not to surrender with his forces or with the Japanese, but rather to escape to Manchuria with a view to seeking a future in the Soviet Union which he believed to be turning anti-British. He died from third degree burns received when his plane crashed in Taiwan.[25][o] Some Indians, however, did not believe that the crash had occurred,[6][p] with many among them, especially in Bengal, believing that Bose would return to gain India's independence.[26][q][27][r][28][s]

The Indian National Congress, the main instrument of Indian nationalism, praised Bose's patriotism but distanced itself from his tactics and ideology,[29][t] especially his collaboration with fascism.[30] The British Raj, though never seriously threatened by the INA,[31][u][32][v] charged 300 INA officers with treason in the INA trials, but eventually backtracked in the face both of popular sentiment and of its own end.[33][w

Biography

1897–1921: Early life

Subhas Chandra Bose was born on 23 January 1897 (at 12.10 pm) in Cuttack, Orissa Division, Bengal Province, to Prabhavati Dutt Bose and Janakinath Bose, an advocate belonging to a Kayastha[34][x] family.[35] He was the ninth in a family of 14 children. His family was well to do.[34]

He was admitted to the Protestant European School (presently Stewart High School) in Cuttack, like his brothers and sisters, in January 1902. He continued his studies at this school which was run by the Baptist Mission up to 1909 and then shifted to the Ravenshaw Collegiate School. Here, he was ridiculed by his fellow students because he knew very little Bengali. The day Subhas was admitted to this school, Beni Madhab Das, the headmaster, understood how brilliant and scintillating his genius was. After securing the second position in the matriculation examination in 1913, he got admitted to the Presidency College where he studied briefly.[36] He was influenced by the teachings of Swami Vivekananda and Ramakrishna after reading their works at the age of 16. He felt that his religion was more important than his studies.[34]

In those days, the British in Calcutta often made offensive remarks to the Indians in public places and insulted them openly. This behavior of the British as well as the outbreak of World War I began to influence his thinking.[34]

His nationalistic temperament came to light when he was expelled for assaulting Professor Oaten (who had manhandled some Indian students[34]) for the latter's anti-India comments. He was expelled although he appealed that he only witnessed the assault and did not actually participate in it.[34] He later joined the Scottish Church College at the University of Calcutta and passed his B.A. in 1918 in philosophy.[37] Bose left India in 1919 for England with a promise to his father that he would appear in the Indian Civil Services (ICS) examination. He went to study in Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge and matriculated on 19 November 1919. He came fourth in the ICS examination and was selected, but he did not want to work under an alien government which would mean serving the British. As he stood on the verge of taking the plunge by resigning from the Indian Civil Service in 1921, he wrote to his elder brother Sarat Chandra Bose: "Only on the soil of sacrifice and suffering can we raise our national edifice."[38]

He resigned from his civil service job on 23 April 1921 and returned to India.[39]

1921–1932: Indian National Congress

He started the newspaper Swaraj and took charge of publicity for the Bengal Provincial Congress Committee.[40] His mentor was Chittaranjan Das who was a spokesman for aggressive nationalism in Bengal. In the year 1923, Bose was elected the President of All India Youth Congress and also the Secretary of Bengal State Congress. He was also the editor of the newspaper "Forward", founded by Chittaranjan Das.[41] Bose worked as the CEO of the Calcutta Municipal Corporation for Das when the latter was elected mayor of Calcutta in 1924.[42] In a roundup of nationalists in 1925, Bose was arrested and sent to prison in Mandalay, where he contracted tuberculosis.[43]

In 1927, after being released from prison, Bose became general secretary of the Congress party and worked with Jawaharlal Nehru for independence. In late December 1928, Bose organised the Annual Meeting of the Indian National Congress in Calcutta.[44] His most memorable role was as General Officer Commanding (GOC) Congress Volunteer Corps.[44] Author Nirad Chaudhuri wrote about the meeting:

A little later, Bose was again arrested and jailed for civil disobedience; this time he emerged to become Mayor of Calcutta in 1930.[43]

1933–1937: Illness, Austria, Emilie Schenkl

During the mid-1930s Bose travelled in Europe, visiting Indian students and European politicians, including Benito Mussolini. He observed party organisation and saw communism and fascism in action.[citation needed] In this period, he also researched and wrote the first part of his book The Indian Struggle, which covered the country's independence movement in the years 1920–1934. Although it was published in London in 1935, the British government banned the book in the colony out of fears that it would encourage unrest.[45]

1937–1940: Indian National Congress

By 1938 Bose had become a leader of national stature and agreed to accept nomination as Congress President. He stood for unqualified Swaraj (self-governance), including the use of force against the British. This meant a confrontation with Mohandas Gandhi, who in fact opposed Bose's presidency,[48] splitting the Indian National Congress party. Bose attempted to maintain unity, but Gandhi advised Bose to form his own cabinet. The rift also divided Bose and Nehru. Bose appeared at the 1939 Congress meeting on a stretcher. He was elected president again over Gandhi's preferred candidate Pattabhi Sitaramayya.[49] U. Muthuramalingam Thevar strongly supported Bose in the intra-Congress dispute. Thevar mobilised all south India votes for Bose.[50] However, due to the manoeuvrings of the Gandhi-led clique in the Congress Working Committee, Bose found himself forced to resign from the Congress presidency.[citation needed]

On 22 June 1939 Bose organised the All India Forward Bloc a faction within the Indian National Congress,[51] aimed at consolidating the political left, but its main strength was in his home state, Bengal. U Muthuramalingam Thevar, who was a staunch supporter of Bose from the beginning, joined the Forward Bloc. When Bose visited Madurai on 6 September, Thevar organised a massive rally as his reception.

When Subash Chandra Bose was heading to Madurai, on an invitation of Muthuramalinga Thevar to amass support for the Forward Bloc, he passed through Madras and spent three days at Gandhi Peak. His correspondence reveals that despite his clear dislike for British subjugation, he was deeply impressed by their methodical and systematic approach and their steadfastly disciplinarian outlook towards life. In England, he exchanged ideas on the future of India with British Labour Party leaders and political thinkers like Lord Halifax, George Lansbury, Clement Attlee, Arthur Greenwood, Harold Laski, J.B.S. Haldane, Ivor Jennings, G.D.H. Cole, Gilbert Murray and Sir Stafford Cripps.

He came to believe that an independent India needed socialist authoritarianism, on the lines of Turkey's Kemal Atatürk, for at least two decades. For political reasons Bose was refused permission by the British authorities to meet Atatürk at Ankara. During his sojourn in England Bose tried to schedule appointments with several politicians, but only the Labour Party and Liberal politicians agreed to meet with him. Conservative Party officials refused to meet him or show him courtesy because he was a politician coming from a colony. In the 1930s leading figures in the Conservative Party had opposed even Dominion status for India. It was during the Labour Party government of 1945–1951, with Attlee as the Prime Minister, that India gained independence.

On the outbreak of war, Bose advocated a campaign of mass civil disobedience to protest against Viceroy Lord Linlithgow's decision to declare war on India's behalf without consulting the Congress leadership. Having failed to persuade Gandhi of the necessity of this, Bose organised mass protests in Calcutta calling for the 'Holwell Monument' commemorating the Black Hole of Calcutta, which then stood at the corner of Dalhousie Square, to be removed.[52] He was thrown in jail by the British, but was released following a seven-day hunger strike. Bose's house in Calcutta was kept under surveillance by the CID.[53]

1941–1943: Nazi Germany

Bose's arrest and subsequent release set the scene for his escape to Germany, via Afghanistan and the Soviet Union. A few days before his escape, he sought solitude and, on this pretext, avoided meeting British guards and grew a beard. Late night 16 January 1941, the night of his escape, he dressed as a Pathan (brown long coat, a black fez-type coat and broad pyjamas) to avoid being identified. Bose escaped from under British surveillance from his Elgin Road house in Calcutta on the night of 17 January 1941, accompanied by his nephew Sisir Kumar Bose, later reaching Gomoh Railway Station in then state of Bihar, India.[54][55][56][57]

He journeyed to Peshawar with the help of the Abwehr, where he was met by Akbar Shah, Mohammed Shah and Bhagat Ram Talwar. Bose was taken to the home of Abad Khan, a trusted friend of Akbar Shah's. On 26 January 1941, Bose began his journey to reach Russia through British India's North West frontier with Afghanistan. For this reason, he enlisted the help of Mian Akbar Shah, then a Forward Bloc leader in the North-West Frontier Province. Shah had been out of India en route to the Soviet Union, and suggested a novel disguise for Bose to assume. Since Bose could not speak one word of Pashto, it would make him an easy target of Pashto speakers working for the British. For this reason, Shah suggested that Bose act deaf and dumb, and let his beard grow to mimic those of the tribesmen. Bose's guide Bhagat Ram Talwar, unknown to him, was a Soviet agent.[56][57][58]

Supporters of the Aga Khan III helped him across the border into Afghanistan where he was met by an Abwehr unit posing as a party of road construction engineers from the Organization Todt who then aided his passage across Afghanistan via Kabul to the border with Soviet Russia. After assuming the guise of a Pashtun insurance agent ("Ziaudddin") to reach Afghanistan, Bose changed his guise and travelled to Moscow on the Italian passport of an Italian nobleman "Count Orlando Mazzotta". From Moscow, he reached Rome, and from there he travelled to Germany.[56][57][59] Once in Russia the NKVD transported Bose to Moscow where he hoped that Russia's traditional enmity to British rule in India would result in support for his plans for a popular rising in India. However, Bose found the Soviets' response disappointing and was rapidly passed over to the German Ambassador in Moscow, Count von der Schulenburg. He had Bose flown on to Berlin in a special courier aircraft at the beginning of April where he was to receive a more favourable hearing from Joachim von Ribbentrop and the Foreign Ministry officials at the Wilhelmstrasse.[56][57][60]

In Germany, he was attached to the Special Bureau for India under Adam von Trott zu Solz which was responsible for broadcasting on the German-sponsored Azad Hind Radio.[61] He founded the Free India Center in Berlin, and created the Indian Legion (consisting of some 4500 soldiers) out of Indian prisoners of war who had previously fought for the British in North Africa prior to their capture by Axis forces. The Indian Legion was attached to the Wehrmacht, and later transferred to the Waffen SS. Its members swore the following allegiance to Hitler and Bose: "I swear by God this holy oath that I will obey the leader of the German race and state, Adolf Hitler, as the commander of the German armed forces in the fight for India, whose leader is Subhas Chandra Bose". This oath clearly abrogates control of the Indian legion to the German armed forces whilst stating Bose's overall leadership of India. He was also, however, prepared to envisage an invasion of India via the USSR by Nazi troops, spearheaded by the Azad Hind Legion; many have questioned his judgment here, as it seems unlikely that the Germans could have been easily persuaded to leave after such an invasion, which might also have resulted in an Axis victory in the War.[59]

In all, 3,000 Indian prisoners of war signed up for the Free India Legion. But instead of being delighted, Bose was worried. A left-wing admirer of Russia, he was devastated when Hitler's tanks rolled across the Soviet border. Matters were worsened by the fact that the now-retreating German army would be in no position to offer him help in driving the British from India. When he met Hitler in May 1942, his suspicions were confirmed, and he came to believe that the Nazi leader was more interested in using his men to win propaganda victories than military ones. So, in February 1943, Bose turned his back on his legionnaires and slipped secretly away aboard a submarine bound for Japan. This left the men he had recruited leaderless and demoralised in Germany.[59][62]

Bose lived in Berlin from 1941 until 1943. During his earlier visit to Germany in 1934, he had met Emilie Schenkl, the daughter of an Austrian veterinarian whom he married in 1937. Their daughter is Anita Bose Pfaff.[63] Bose's party, the Forward Bloc, has contested this fact.[64]

1943–1945: Japanese-occupied Asia

In 1943, after being disillusioned that Germany could be of any help in gaining India's independence, he left for Japan. He travelled with the German submarine U-180 around the Cape of Good Hope to the southeast of Madagascar, where he was transferred to the I-29for the rest of the journey to Imperial Japan. This was the only civilian transfer between two submarines of two different navies in World War II.[56][57]